Today’s animal is the mighty lion. A few weeks back, we talked about the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh and also his stone-carving of Sennacherib’s gardens, but he is also famous for the magnificent sequence of stone-carvings of a royal lion hunt.

We all know the lion in heraldry, from the three lions of the England football team to the British royal coat of arms. The lion as a heraldic symbol of royalty was imported to Western Europe from the ancient Near East by the crusaders. This association of royals with the lions themselves is actually an inversion of the original symbolism. The Sumerian king was not a lion; he was the shepherd, defending his flock from the threat of wild animals, though this inversion was already common among the later Assyrian kings. Ashurbanipal was not a warrior in the same way as his predecessors – he wasn’t all about taking the fight to his neighbours. His way of showing strength then, was through participation in the Assyrian sport of kings – the “hunting” of captured lions.

Like matadors in Spain, the risk to Ashurbanipal was hugely reduced by weakening the beast from a distance before approaching to kill it with a sword. Not long after I first moved to Spain, I spent a few hours sinking cañas on a hot summer day in a bar in Madrid’s Plaza del Sol. The bullfights were on the TV, and I drank surrounded by enormous, woolly-haired heads and thick necks of the dispatched victims of earlier fights. It’s a fearsome slow spectacle that raises the adrenaline, but feels awful and utterly wrong as you watch the creature stagger and sway, the blood dripping from his flanks. It seems like an age before the matador finally steps in for the arranque, cruce, y salida (start, cross, and exit) that make up the three steps in the kill. I’ve never seen a bullfight in person, and despite having been an avid reader of Hemingway in my teens and twenties, I don’t think I could handle it.

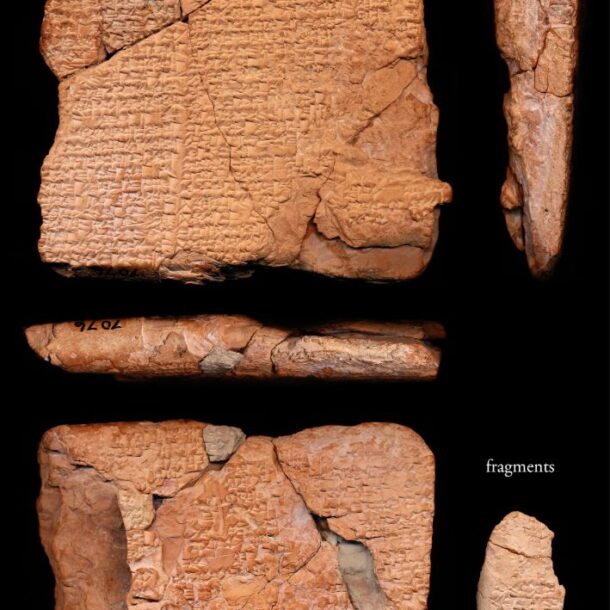

Fighting and killing lions was a symbolic part of kingship in ancient Mesopotamia (at times at least), and perhaps more of a real duty of protection in the earlier times than the staged events of the Neo-Assyrians. Today’s tablet is part of a praise poem for Shulgi, king of Ur from 2094 to 2047 BC. In it the king speaks:

“I stride forward in majesty, trampling endlessly through the esparto grass and thickets… and I put an end to the heroic roaring in the plains of the savage lion, dragon of the plains, wherever it approaches from and wherever it is going. I do not go after them with a net, nor do I lie in wait for them in a hide; it comes to a confrontation of strength and weapons. I do not hurl a weapon; when I plunge a bitter-pointed lance in their throats, I do not flinch at their roar. I am not one to retreat to my hiding-place but, as when one warrior kills another warrior, I do everything swiftly on the open plain. In the desert where the paths peter out, I reduce the roar at the lair to silence. In the sheepfold and the cattle-pen, where heads are laid to rest, I put the shepherd tribesmen at ease. Let no one ever at any time say about me, ‘Could he really subdue them all on his own?’ The number of lions that I have dispatched with my weapons is limitless; their total is unknown.”

In case this fragment of kingly braggadocio isn’t leonine enough for you, you can go see Ashurbanipal’s hunt for yourselves in Room 10a of the British Museum. Although it’s still closed you can see inside the museum on Google Street View, and I highly recommend the trip.