Today’s tablet tells the story The Great Fatted Bull. That’s doubly appropriate today: first because it’s an animal story from ancient Mesopotamia, but also because it’s my birthday and so I will undoubtedly be a fatted Bull by sundown.

Before we get onto the GFB, I want to mention the emergence of birthday celebrations. Herodotus (if you believe a word that unreliable Greek has to say about the Near and Middle East) would have it that it was the Persians in the 5th century BC who began the tradition of feasting on each anniversary of one’s birth. By the 2nd century AD, the Romans were doing so too. In Plautus’ comedy Pseudolus, a birthday boy states, “I wish to entertain tip-top men in first-rate style, that they may fancy that I have property.” These Greeks, Romans, and Persians were late to the party though. It appears that birthday feasts were something of a tradition during the famously unkind and corrupt reign of Lugalanda of Lagash, way back in the 24th century BC. Various accounts tell of feasting to mark births into the royal family, including a list of feasting supplies, collated by a tax collector and a cattle-fattener.

Which makes the perfect segue to our Great Fatted Bull.

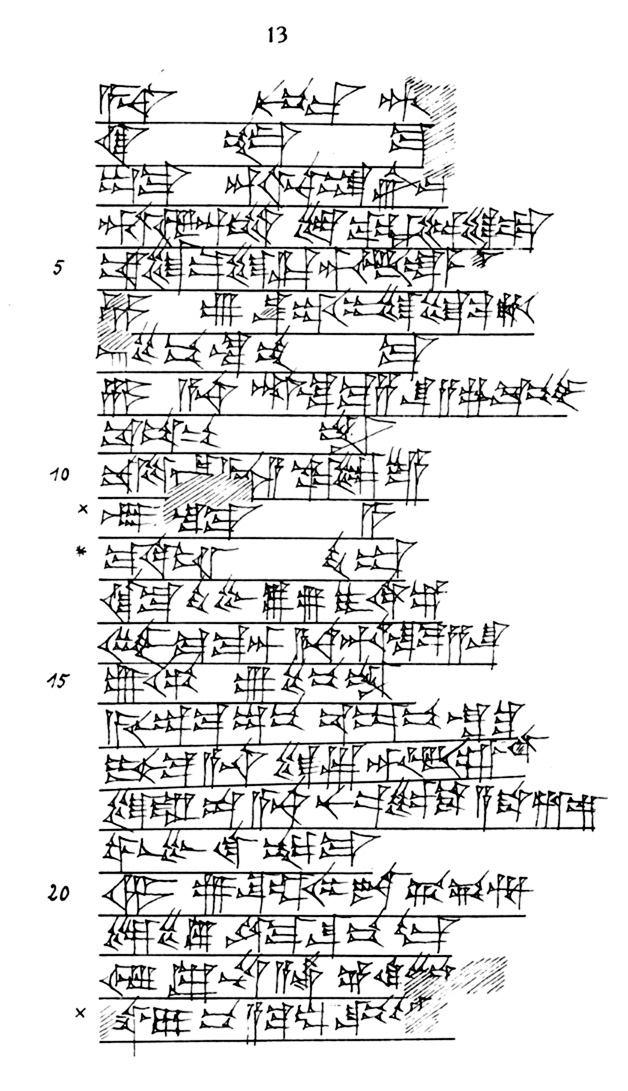

Another invention claimed for the 5th century BC, this time by the ancient Greeks themselves, was the political satire. If we are to believe the amateur Sumerologist, Jerald Jack Starr, the credit belongs to the anonymous author of Tablet #36, which he has translated as the story of “Great Fatso”. Lu-mah is Fatso’s real name. It means “great man”, but he is in fact a bull. His name though is disguised; the sign used for the sound “mah” is not the correct one in this context, but a meaningless homophone. It’s not the best piece of cryptography, but it suggests that the writer was trying to disguise the target of his work.

This use of homophones has more recently been exploited by Chinese online satirists and meme creators – and that’s meme in the internet sense this time, not that of Richard Dawkins. Behind the Great Firewall, these internet dwellers use the characters for “mud river horse” (a homophone for “fuck your mother”) to protest the “river crabs” (a homophone for “harmonize” used as slang for “online censors”). There’s even an algorithm developed by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology which takes a word which would normally be automatically flagged on Sina Weibo (the Chinese equivalent of Twitter) and renders it as a superficially meaningless homophone.

Back to our story. Great Fatso spends the first side of the tablet stomping around, gobbling up land and grain, bedding his wife and taking slave-girls, all the while bellowing his good intentions to provide for his old mum. He orders a captive father to trample his field no. 5, then forces the son, a shepherd, to buy the field back in return for all his stored grain. An unsympathetic beast of a character then, meant to represent a bad king in the style of Lugalanda. On the reverse of the tablet, the shepherd son (the hero, representing a good king) stands up to Fatso,

“I will not bow before the man who seizes everything but wisdom. He is not a strong man.”

For this impertinence, the bad king beats him like an angry storm and leaves him for dead.

Scene change: a victory feast, the Great Fatted Bull pigging out on grain, choking on fat handfuls. A man sneaks in through the window – who else but the good shepherd? They fight, and throttle one another almost to death. Seeing he is beaten, the bull pledges to give up his mountain of grain and rein in his appetites. His family turn on him (his own mother says she doesn’t place much trust in him), and side with the captives and the shepherd. The bull is sent away to marry the owner of field #4, where he is happy for while until he makes eyes at the woman in the neighbouring field…

There the tablet breaks off, but I think we can all see where it’s going.