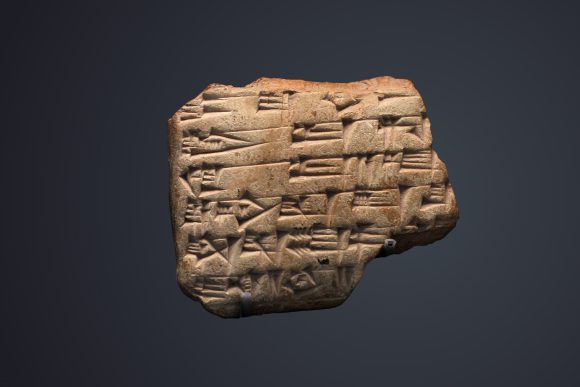

This week we’re going to be seeing a whole lot of creatures that inhabited the Mesopotamian landscape. Understanding what creature was meant by a combination of wedge-marks in clay, or of syllables is a monumental task. Even today, there are a hundred different names for the same species of fish or flower, depending on whom you ask. As Benno Landsberger, godfather of the study of Mesoptamian fauna and flora, puts it, “One of the major problems is the disparity between Linnaean nomenclature and that of the marketplace, ancient and modern”. This Linnaean, or Latin name, is nowadays the key that lets us tie together various mentions of a creature as a food item, a companion, or a provider of some essential role in an ecosystem, but the Mesopotamians obviously had no such system.

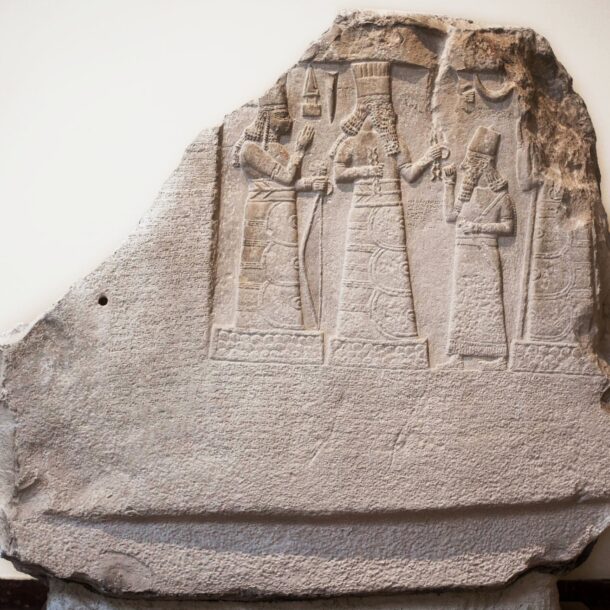

Today’s stele is of a historical figure who brought honeybees (Apis mellifera) to a new land. Shamash-resh-ușur was the governor of Suhu, a region which included Mari (day 55) in modern Syria. He writes in the inscription that he introduced honeybees to the orchards of Suhu, carried “from the mountain of the men of Habha”. Another bee-carrying story comes from the Book of Mormon (not the musical). During the Jaredite’s migration from the “great tower”, supposedly the Tower of Babel (day 42), The Book of Ether tells, “They did carry with them deseret, which by interpretation, is a honey bee”. Deseret, the bee on the seal of the State of Utah, is supposedly a Jaredite word, and was actually proposed as the name of the state itself.

The naming of things had a magical power to the Sumerians who, as we’ve seen, assigned great importance to the etymologies of words. There’s something psychologically true about this, which we see reflected in folklore – think Rumpelstiltskin – and in modern literature. In The Rule of Names, Ursula K. Le Guin’s schoolteacher tells the class, “You never ask anybody his name. You never tell your own.” True names give power over things, and power over people too.

Staying with bees, Henry Reed’s The Naming of Parts works because of the power of double meanings of names. The spring of a bolt-action rifle, and the Spring which has the bees going backwards and forwards to the almond-blossom:

They call it easing the Spring: it is perfectly easy

If you have any strength in your thumb: like the bolt,

And the breech, and the cocking-piece, and the point of balance,

Which in our case we have not got; and the almond-blossom

Silent in all of the gardens and the bees going backwards and forwards,

For today we have naming of parts.

The Naming of Parts, reads like a spell. Naming things brings order to the chaos of war, but the incongruous location of a country garden keeps slipping into the foreground, the hum of bees like the buzzing of ears after an artillery shell lands too close. Both meanings are equally true, equally real, all at once.

It is, by now, a trope that true names give power. The true names used to summon demons are often Latin, as though of all the languages that fell out of the Tower of Babel, Latin was the one that stuck. Isn’t it a wonderful coincidence that the names which gives us the most power to understand fish and plants are also now their Latin names?