We started the week with the oldest profession in the world, and we’re ending it with one which has been called the second oldest, and less reputable profession – espionage.

It’s in equal parts frustrating and comforting to see that other researchers have the same struggle over finding images of specific tablets mentioned in earlier books and articles. The historical facts and quotations from cuneiform letters I’m writing about today are largely drawn from a report produced by Col. R.M. Sheldon for the CIA’s Historical Review Program in Spring of 1989. In her report, she discusses the difficulty of tracking down an image of what may be the first “classified” document. The tablet was transcribed by the French archaeologists working at Mari (day 55), but the team were unable to locate any photographs.

Mesopotamia, the land between rivers, has been plagued by clouds of gnats both literal and metaphorical for thousands of years. The head of King Shamshi-Adad’s spy bureau at Shubat-Enlil was named Buqaqum, or “little gnat” – as Sheldon puts it, he was the original of “the proverbial fly on the wall”.

There is another relatively well-known spy (possibly not the best things for a spy’s CV) who practised her tradecraft in the Mesopotamian sphere of operations. Grace Bell was a colleague of T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) and provided boots-on-the-ground intelligence rather than the historian’s perspective that Sheldon provides. She was also in the position of being able to talk with women such as the wives of tribal leaders, opening up a valuable line of intelligence that wasn’t available to the graduates of public boys’ schools in England that made up most of the British gnats in the region.

This world of spies was in no way new in the time of Bell and Lawrence. Shamshi-Addad in a letter to allied kings of neighbouring cities wrote:

“All of you are constantly trying tricks and manoeuvring endlessly to destroy the enemy. The enemy likewise constantly tries tricks and endlessly manoeuvres against you, just as wrestlers try to trick one another all the time . . . I hope that the enemy will not manoeuvre you into an ambush.”

He would well have known about the kind of tricks and manoeuvres. His sons conducted what we’d nowadays call a false flag operation “attacking a territory with a group of guerrillas formed by their own men disguised as the opposing force.”

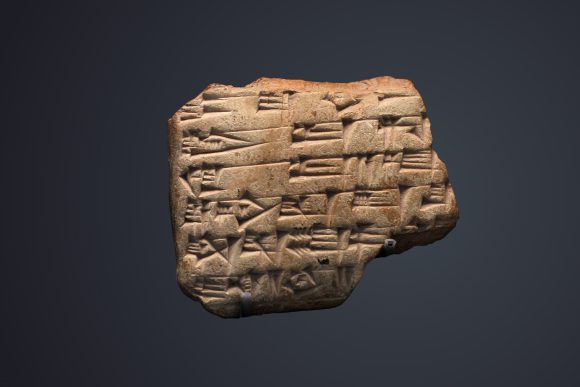

Knowing that the CIA couldn’t track down the classified tablet I mentioned at least meant I could stop trying and look for something easier. So today as a poor second-best, I present to you a tablet relating to Zimri-Rim, who took the kingship of Mari from Shamshi-Addad’s sons during the reign of Hammurabi in Babylon. Feel free to ignore it, it’s not too related to our topic. Turning back to the elusive classified document I mentioned. The document was an order to disappear a man who had been causing trouble of some unspecified nature, reading: “If there is a ditch in the countryside or in the city, make this man disappear into it.” The document was marked at the top with the words “THIS IS A SECRET TABLET”. That reminder was backed by some serious consequences. Punishment for leaking was for the leaker, their co-conspirators, and their household to be set on fire.

When Colonel Sheldon wrote of the difficulty of sustaining excavations of the sites of Mari and Shubat-Enlil “[b]ecause Mesopotamians are still fighting Persians”, she was writing during the Iran-Iraq War, prior to the first Gulf War. Over thirty years later, the region of northern Iraq and Syria is scarcely more peaceful. The “SECRET TABLET” was last known to be in the Syrian National Museum at Aleppo, but was likely evacuated a few years ago before the museum was hit by missiles. Let’s hope that someday peace will return to the region and cultures old and new can once again be celebrated.