In the Louvre, there is a statue of King Gudea of Lagash known as “The architect with a plan”. This statue, like many of those of Gudea, is made of the black stone diorite. The king was clearly whatever the stone-carving equivalent is of photogenic, since he commissioned many sculptures. The architect with a plan sculpture is described as “acephalous” in one sesquipedalian description I read, which raises the intriguing possibility that it’s the same headless statue as that found by William Loftus. But since there are at least two life-size heads of Gudea in collections at the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid and the Met Museum in New York, it’s a 50:50 chance at best.

Gudea considered himself a builder king rather than a warrior king, and so he’s depicted seated on a throne/stool with an architectural drawing and architect’s tools in his lap. This statue, as well as containing the earliest recognisable architectural plan, also has the longest known inscription in Sumerian, detailing the building of the huge temple in the drawing, and the sources and types of materials used in its construction. It’s every inch the plans and specifications for a great public work, though seemingly created after the fact as a record rathe than as a design.

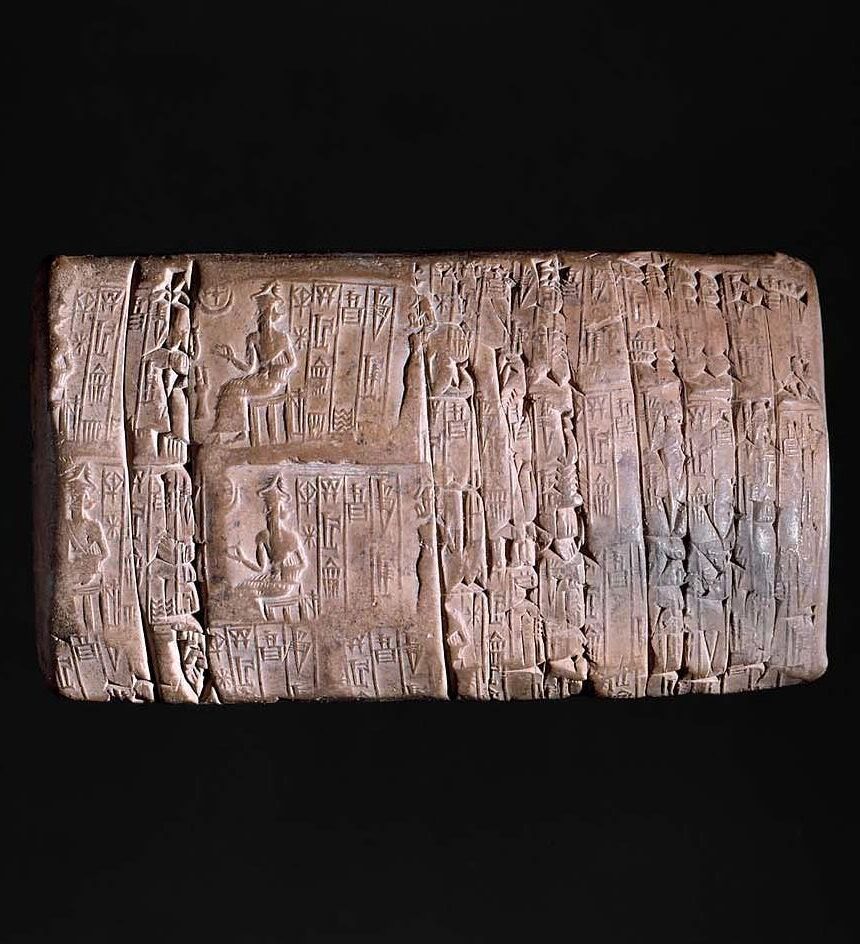

Today we’re looking at the profession of architect by looking at the artifacts they left behind. The Schøyen Collection contains five Mesopotamian artifacts with architectural drawings, including the Tower of Babel stele we saw on day 42, as well as today’s tablet. In all, around 40 architectural drawings are known from cuneiform cultures. What I love about today’s piece is how modern it looks. The conventions of simple architectural plans are followed, with double-lines for walls, spaces for doorways, dimensions of rooms. What we don’t know is why this and similar drawings were made, and by whom. We’ve been assuming it was the work of an architect and produced as part of the design process, but it could equally have been a surveyor producing documentation of a property for sale. It reminds me of the kind of plan you’d see in an off-plan listing for a new home on an estate agent’s website.

“This listing is for a house in up-and-coming Umma, measuring 20 cubits by 25 cubits gives you around 500 square cubits of usable floor area. The heart of the property is the 84 square cubit central courtyard which gives on to six surrounding rooms in a harmonious arrangement of spaces to make your own. It will make the ideal home for you and your growing family. Send your house-servant now to register your interest.”

The drawing on the tablet is done to scale, which might explain why there is so much empty space around the actual plan. Given the sexagesimal number system used by the Sumerians and later Mesopotamians (and by us for degrees of a circle), it’s perhaps not surprising that the scale is 1:180; one cubit of the building is about 27 mm on the plan. This becomes really interesting when you take a closer look at the statue of Gudea in the Louvre. This statue is life-size, and the measuring stick on its lap has small gradations marked at 27mm intervals. There are two other drawings of the period which use this same scale, so we can tentatively conclude that it was some kind of standard scale.

This cultural invention of plans drawn to scale as though viewed from the sky is yet another that has been passed down to us from Sumerian beginnings. While it has undergone huge leaps in the past few years since the advent of 3D drawing software like Revit, architects using board and paper or 2D software packages like AutoCAD continue to follow the same patterns of drawings as those of the architects of Umma and Lagash. To misquote Christopher Alexander’s title, it’s a timeless way of drawing a building.