No jokes today. No glib cultural references. I spent quite some time trying to decide whether or not to write this piece this week, since it feels wrong to consider “slave” as a job or profession. It was certainly an occupation, the means by which people earned their bowl of grain. In Sumerian documents it is attested in various forms including indentured slaves, bought slaves (usually prisoners of war), and those born into slavery.

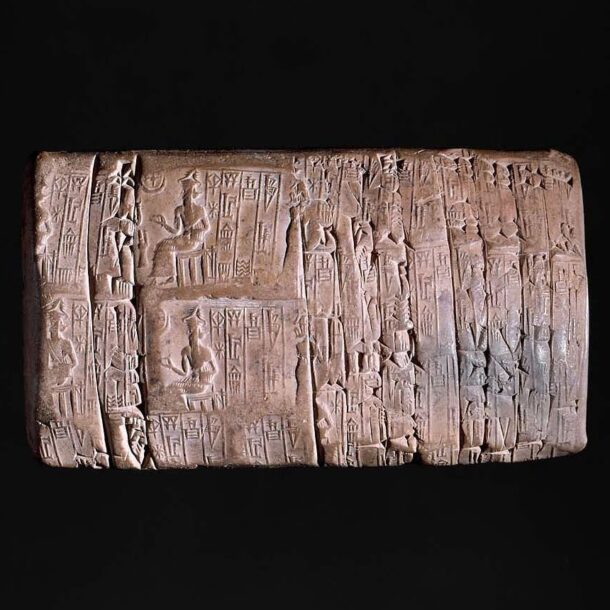

Today’s tablet with its beautiful illustration is from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. It’s one of around thirty cuneiform objects in their Ancient Egypt, Nubia and the Near East collection, purchased through the Frederick Brown Fund. Which Frederick Brown? Given that we’re talking about gifts to an American museum, it could be Frederick Brown, the Chicago-born African American artist working in the late 1960s to the early 1990s. Among other works, he painted John Henry, a portrait of the legendary freed slave and steel-driver who died in a race against a steam-hammer. In Brown’s painting, he is reimagined as a steel worker in the steel-mills of South Chicago. But from the dates of the fund’s various gifts, it was purchased in the name of Frederick Brown, the British professor of art who died in 1941. It’s important to follow these threads and to avoid well-meaning but misplaced raising of black voices. Getting it wrong only gives ammunition to those who would rather the voices stay silent.

Staying in Boston (and Nubia), another arguably misplaced gesture is the renaming of Dudley Square to Nubian Square. This action was taken on the allegation that colonial Governor Thomas Dudley perpetuated slavery. The case for Dudley’s defence is his role in the drafting of a charter of freedoms which contained the line, “There shall never be any bond slaverie, villinage or Captivitie amongst us unles it be lawfull Captives taken in just warres, and such strangers as willingly selle themselves or are sold to us.” For the American colonies in 1661, this was progressive stuff. Not so progressive that it goes much beyond the laws under Hammurabi in Babylon over 3000 years earlier, but if you consider that the Royal African Company was founded a year earlier in 1660, and went on to ship more African people into slavery that any other institution, you get a picture of the times in which Governor Dudley was writing.

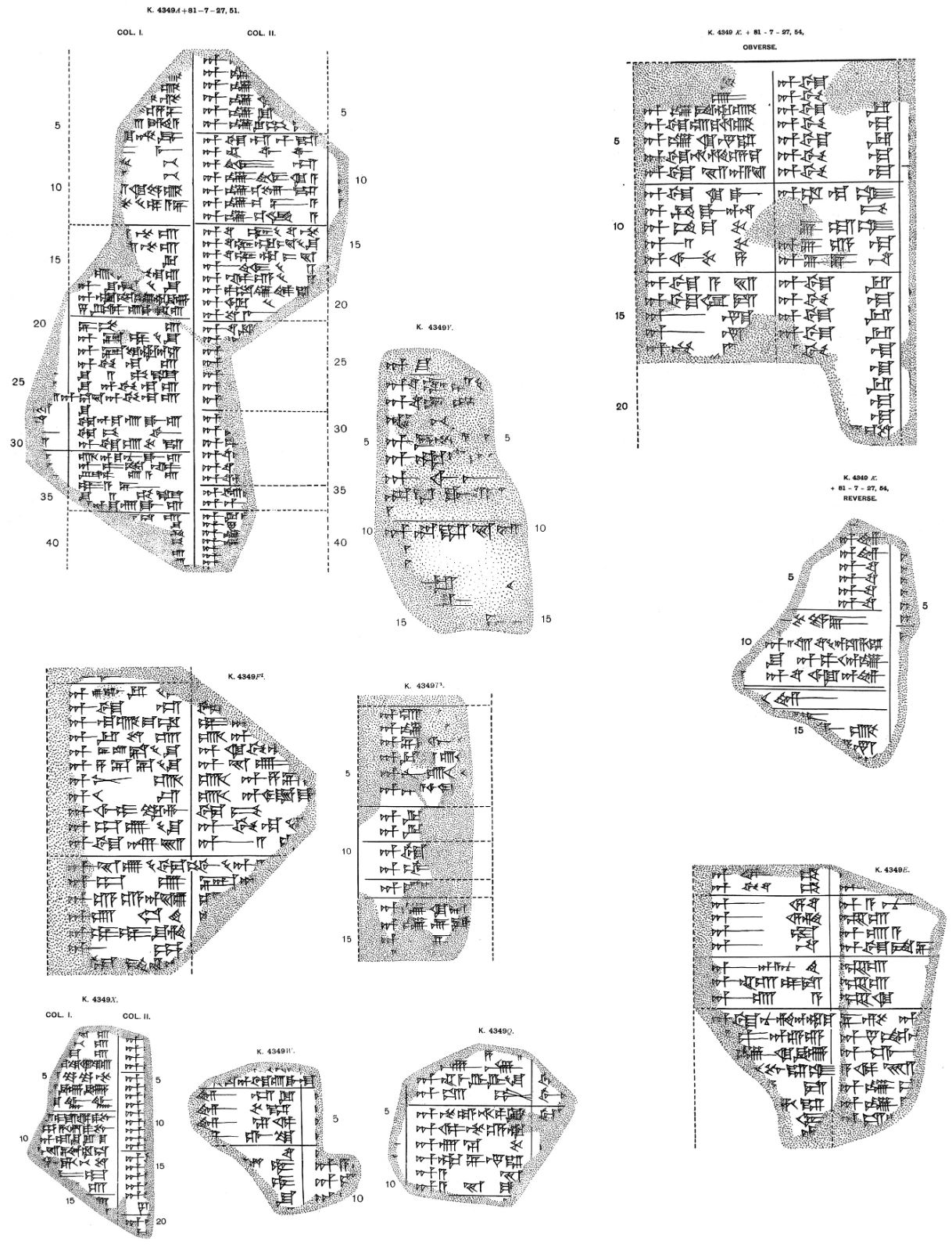

That phrase “just warres” though. It raises the obvious question, what is a just war? Prisoners of war were one of the main sources of slave labour in Sumer, but as we’ve seen, the wars were often far from just. Kings would lead their armies on raids of near and distant lands, returning with captured slaves particularly from the mountains. The Sumerian signs for slave actually consist of the sign for “male” or “female” combined with the sign for “mountain”. These prisoners of “war” are the closest parallel of the people trafficked across the Atlantic. Pulled from the land as though they were a natural resource to be harvested. Black gold to drive the engines of agriculture in Mesopotamia and Virginia.

So was Governor Dudley an ally? Should his former square be returned to his name? People have pointed out that slavery, and even ritual sacrifice of slaves, was practised in the Nubian Empire so was that the best new name for the square? For what it’s worth, I’m going to say yes. Both sides can argue “it was a different time”, but Dudley and his colonial compatriots have long enjoyed their time in the sun. The newly-named Nubian Square is proving to be a rallying point for Black Live Matter protests, amplifying ignored voices, and reminding people of all colours that there was a thriving and powerful civilisation in Africa long before the sun rose on the American colonies.