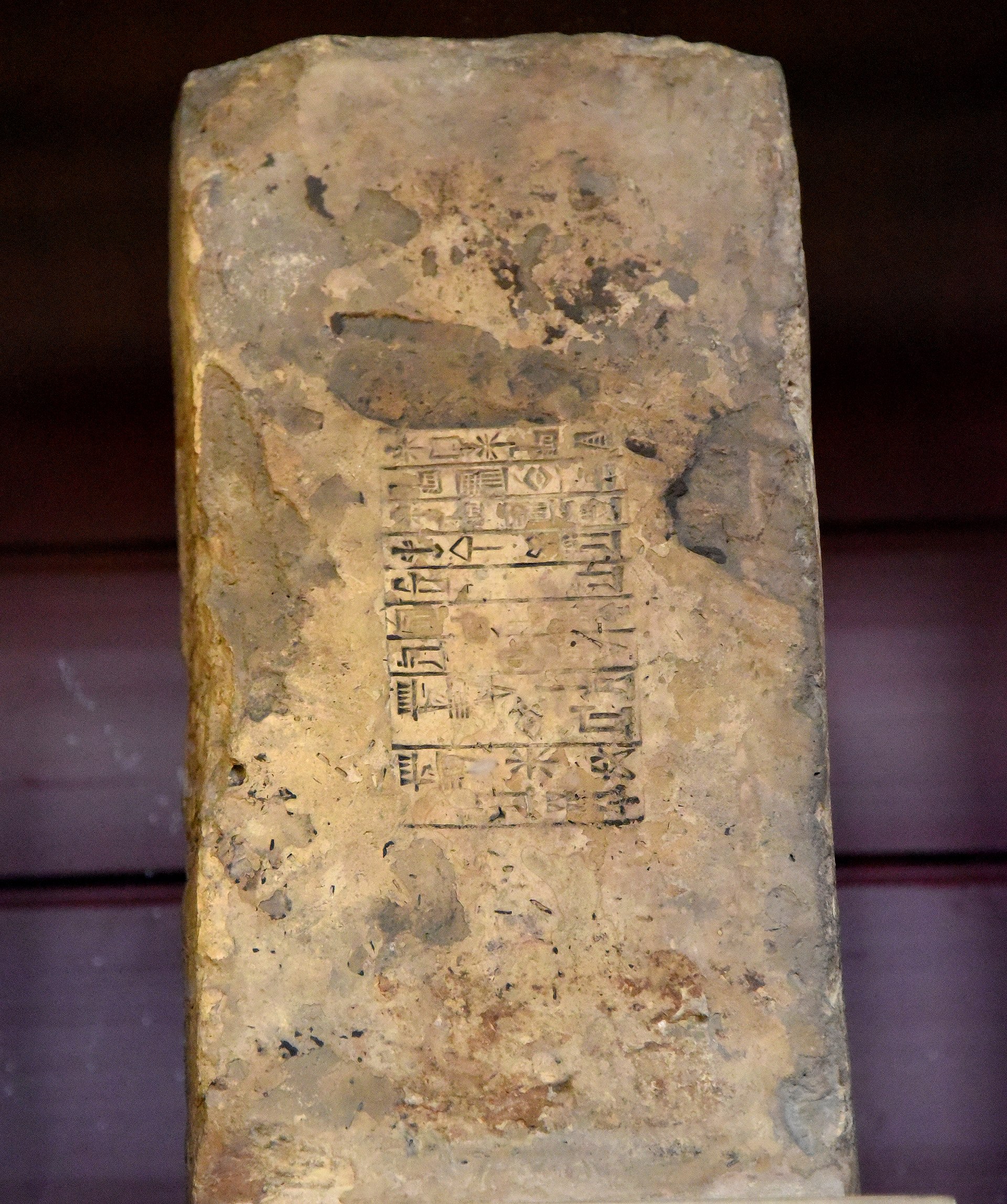

Today’s tablet is more of a treasure than anything John George Taylor could have hoped to have found buried beneath a ziggurat. This piece is attributed to the city of Sippar, 60 km north of Babylon, but records of the locations of finds were not great back in the late 19th century. It could also have come from Sippar’s twin city, Sippar-Amnanum. It may even have come from Borsippa if the name of the scribe’s ancestor, given in the colophon, means he was related to the scribe Ea-bel-ili of Borsippa. But lets say Sippar, as that’s the common consensus.

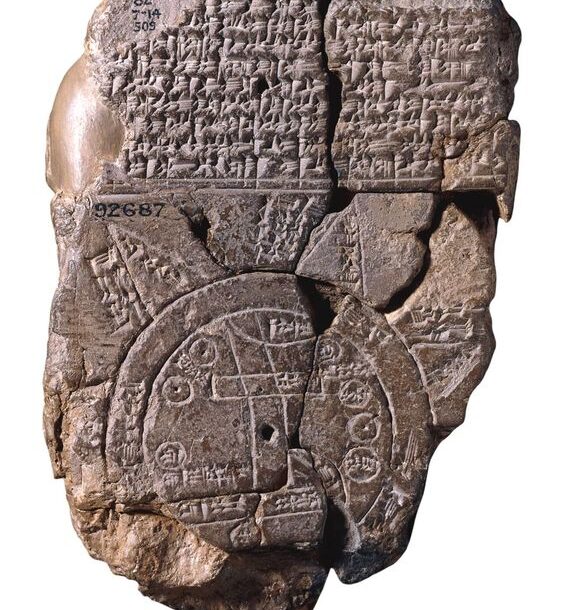

The tablet is a map of the known world in the Neo-Babylonian period, known as the Babylonian Mappa Mundi. It’s no Google Maps, lacking as it is in satellite precision and comprehensive detail. It’s not even Apple Maps, although it does have some landmarks shown in quite the wrong place. If this is the kind of map Moses was working with, it’s no surprise he wandered the wilderness for 40 years on what Google Maps tells me is no more than a 10 day walk from Cairo to Jerusalem, even with the detour to Mount Sinai to pick up some commandments.

But maps are models, mental models that allow us to place order on the world, allow us to “travel without moving” as Jamiroquai put it in a phrase borrowed from Frank Herbert’s Dune. It has been clear over the last few months of pandemic that models are not always reliable, but in the famous words of George Box, “all models are wrong, but some are useful”.

So what use would this map of the world have been to the people of Sippar? The map consists of a central continent with familiar landmarks, surrounded by a circular “bitter river” or ocean, with distant lands marked around the outside. The text on front of the tablet describes the beasts that come from these distant lands, and their place in Mesopotamian literature. The back of the tablet describes the remote and mysterious regions “whose interior no one can know”. Like the way world maps from the USA place the Americas at the centre, and British Empire maps show the UK in much greater detail than India, maps and other models reflect what we think is important. By necessity, the Babylonian Mappa Mundi has more detail of the inner continent – it is after all what they knew. But the text is much more interested in the outer regions, reflecting the thirst for discovery at the start of the first millennium BC.

I want to touch last on two phrases from the Polish-American physicist and philosopher, Alfred Korzbyski. He is famous for writing “the map is not the territory” and “the word is not the thing”. We know that for Mesopotamians, in many ways the word was indeed the thing. The name was indistinguishable from the concept. Did they see maps in the same way? In child development, there is a phase where they move from navigating the world by sight, and so can’t always trace their route back in the opposite direction, to a map-in-the-head metaphor. This doesn’t appear until they have been exposed to real-world maps. There were other maps in Mesopotamia, but of smaller areas like a town. Perhaps this tablet marks a phase where this map-in-the-head became an extended metaphor.

Looking back to these distant times, can we really hope to understand the minds of the people? Were their thought processes like those of children? Are the glacial steps in cultural development the same as those our children now flicker through in mere months? As we read and interpret their writings and artifacts, are we getting closer to a satellite view of their lives, or are we only at the coastline of a land “whose interior no one can know”?