Multiple excavations at Eridu, from the first in 1855 to the last which ended in 1949, found archaeological evidence of shrines on the site, going back over 6,500 years as far as the Ubaid period. Mythologically-speaking, Eridu and not Uruk was the oldest city – the city of the first kings. The Sumerian Kings List opens:

“When kingship from heaven was lowered, the kingship was in Eridu.”

It may be that it was the longest continuously occupied settlement, but it didn’t clear the bar to become a true city until later than Uruk.

Eridu was a great city from the early days of Sumer. Close to modern-day Basra, it sat at the meeting point of salt marshes, river flood plain, and semi-desert. It was a meeting point for the peoples who made their living in these three very different environments, all seeking access to the fresh water of the aquifer.

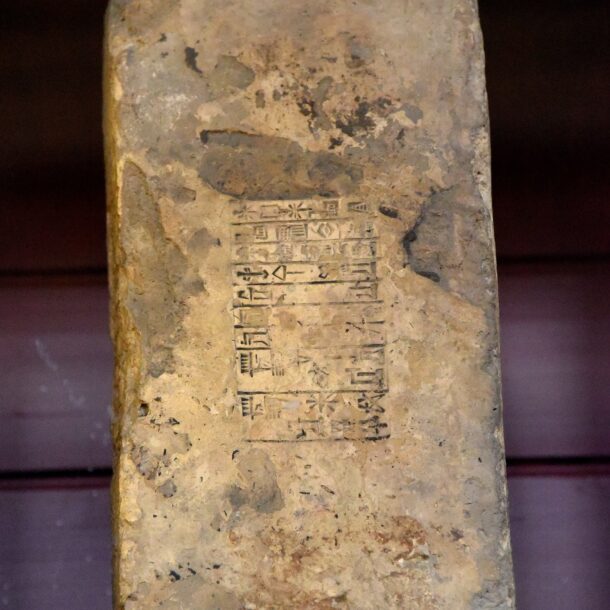

The city grew up around a depression in the desert where fresh water rose from the aquifer that lay beneath ancient Sumer. Mudbrick temples, eighteen layers of them, have been excavated on the site. At least the later of these were dedicated to the god Enki, and named E-abzu, House of the Aquifer. When Amar-Sin came to power, following on the heels of his father Shulgi (more to come from him on day 69), he undertook a project of renewal of the ancient sites of the Neo-Sumerian Empire including Eridu. He looked upon this heap of layer upon layer of temples and thought, “I really, really, really want a ziggurat, ah”. Or words to that effect.

Today’s stamped and fired brick comes from these works, but unfortunately for proto-Scary Spice, Eridu was abandoned during his reign. The ziggurat of Eridu was never completed. Increasing salinity of the soils from repeated irrigation with the slightly salty waters from the river is thought to have reduced the productivity of the fields to the extent that they could no longer support the city.

But what was a ziggurat? What purpose did they serve? For the first generation of modern archaeologists, inspired by recent dazzling finds in Egyptian pyramids and mastabas, the obvious purpose was some kind of burial mound. John George Taylor, one of the pioneers of archaeology was much-influenced by the long tradition of treasure-hunting. In 1855 he conducted what by modern standards was a brutal full-frontal assault on the ziggurat, digging pits and trenches in a haphazard manner, and showing great regret that the only treasures he uncovered were wall paintings “of extremely rude execution”.

We now know this lack of treasures is typical of ziggurats. There are around 25 of them spread evenly distributed from south to north across Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria, and current thinking is that they were built as a dwelling place for each city’s patron god. Each ziggurat may have been topped with a shrine. According to Herodotus (and no one else, surprise surprise) the one at Babylon had a golden couch on which a woman would spend the night alone with Marduk, tutelary deity of the city. No remains of such a shrine have ever been found, but perhaps this time we can give our unreliable friend Herodotus a break. The tops of all the ziggurats we know of have long since eroded away, along with any evidence of what might have been placed there.

Out of myth, desert, and aquifer, the city of Eridu and the pinnacle of its ziggurat grew layer upon layer, and yet never reached completion before it began to melt back into the sands. So near yet so far, like abandoning this challenge on day 179.