I already wrote about the Uruk Period (4000–3200 BC), back on day 23, but today I want to write about the city for which the period is named, and about cities in general and what they did to society.

What defines a city? According to the influential sociological definition given by L. Wirth:

“For sociological purposes a city may be defined as a relatively large, dense, and permanent settlement of socially heterogenous individuals.”

Beyond this, there is the “functional” definition of B. Trigger, which states:

“It is generally agreed that whatever else a city may be it is a unit of settlement which performs specialized functions in relationship to a broad hinterland.”

These two overlapping definitions are sufficient to let us call Uruk the first city.

This specialisation of roles leads, seemingly inevitably, to differentiation and classification. Difference in function implies difference in value to society, fairly or unfairly. Marx had a thing or two to say about this division of labour, as did Adam Smith. Both saw that there are positive effects and also inherent risks in this process. Giving up some of one’s freedom and work product in return for protection, and organisation of works by rulers and overseers may at certain times have been a great deal; at others a coercive and one-sided relationship.

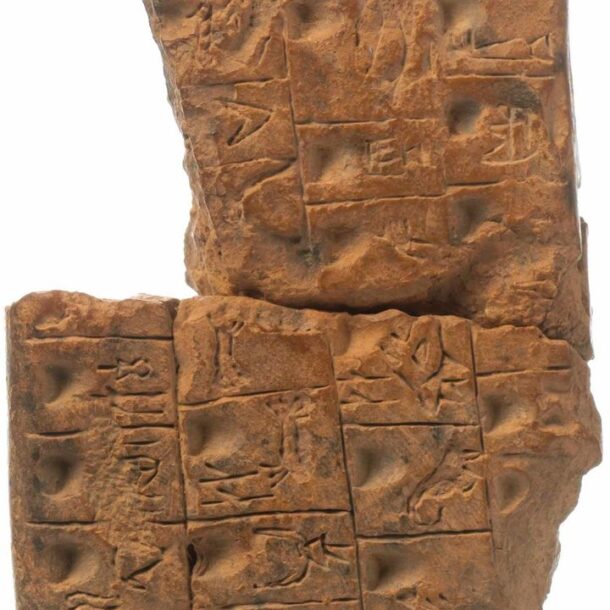

In a graphic illustration of this division of labour, Uruk is the source of the earliest versions of the Sumerian Titles and Professions List. Today’s tablet is an early version of the list at the Vorderasiatisches Museum, in Berlin. More complete examples of the list contain logograms for many differentiated roles and professions, organised in a way that implies they were ranked according to their place in society. A kind of caste system, or at the very least a class system. It begins with high political titles and works down through supervisory roles to skilled professions like smith, potter.

At the very bottom of the list were people “kept like animals”, the equivalent of slaves. These were prisoners of war, convicted criminals, or those heavily in debt. Those who would minimise the horrors of transatlantic slave trade often argue that slavery was nothing new, that slavery has always happened, all throughout history. By one measure this is true; slaves certainly existed and were bought and sold as property, as evidenced by many records of sales. But there is a qualitative difference between a society which has slaves and one which depends entirely on slaves for its functioning. The classical scholar Moses Finley argued that there have only been “five genuine slave societies” in human history: the Roman Empire, ancient Greece, and more recently the Caribbean, Brazil, and the United States. There are those who would argue that the prison system in the USA is a form of modern-day slavery, where prisoners are forced to work for no recompense beyond food and somewhere to sleep. This is actually a surprisingly close parallel to the place of slaves in Uruk, held as they were in the bit asiri or “house of prisoners” (day 60), but it is clearly not on the same scale as the industrial usage of human beings in the New World plantations.

Cities imply specialisation of roles; specialisation leads to a classification of society; class societies place outsiders and transgressors on the bottom rung; and that bottom rung is indistinguishable from slavery, then as now.