Today’s royal subject is Sargon of Akkad (regnal dates 2334 – 2284 BC in the middle chronology). Sargon was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire (day 25), and arguably the first ever emperor of anywhere. He marked his conquest of the entirety of Sumer by washing his hands in the “lower sea”, meaning the Persian gulf, reminiscent of Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s dream that Russian soldiers would one day “wash their boots in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean”. In case you’ve not heard of him, Zhirinovsky is the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, yet another example of why you should be suspicious when an organisation feels the need to put “Democratic” in the name.

There were three Sargons in ancient Mesopotamia, which causes some confusion. Despite the Sargon we’re talking about today being the earliest of the three, he’s not the same as Sargon I of the Assyrian Empire. He’s also not Sargon II from the Hebrew Bible. He is, however, the same Sargon as featured in The Scorpion King: Rise of a Warrior, although that portrayal is somewhat less than faithful to the historical facts. This is a shame, since the facts (ok, legends) as we have them today, are worthy of movie treatment.

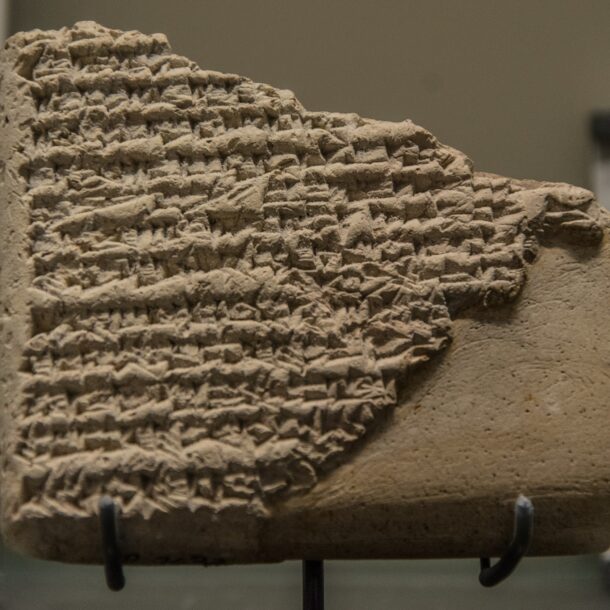

Sargon was not born into power; the Sumerian Kings List calls him the son of a gardener. Today’s tablet is not in the least contemporary, dating from 1600 years later, but is supposedly autobiographical. It contains an origin story remarkably like that of Moses, in which the baby Sargon is placed in a basket of rushes and floated down river. It hardly needs pointing out, this is almost certainly legend. But if you were making the movie, you wouldn’t leave it on the cutting room floor.

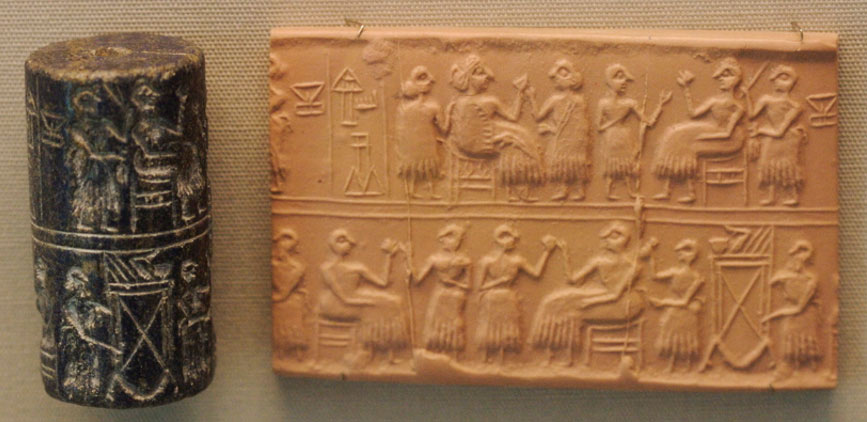

What we are told about Sargon’s ascent to power is that at some point, for some unknown reason, he was appointed as a cupbearer to Ur-Zababa, king of Kish. While in this role, Sargon had a dream in which Ur-Zababa was drowned in a river of blood by the goddess Inanna (yes, her again). The king had also been plagued by nightmares, and on being told about Sargon groaning in his sleep, brought him to be questioned about his dream. Sargon tells the king about a young women (Inanna): “For me, she drowned you in a great river, a river of blood”. Unsurprisingly, this omen leads the king to fear for his life and in what would make for a gripping scene, orders his chief bronze-smith to murder Sargon by casting him into a bronze mould. But Inanna had other plans. Like a glassmaker’s furnace (day 11), the smithy was also a sacred house. Before he got close, Inanna barred Sargon from entering since he was “polluted with blood”, thus saving him from his fate in the fire.

But that wasn’t the end of it. About a week later, Ur-zababa hatched a new plan. He dispatched Sargon with a message for Lugal-zage-si, king of Uruk. This letter had no envelope, but this was no use to Sargon who would have been illiterate; he would not have been able to read the order that Lugal-zage-si should murder him on arrival. Just imagine this. You’re carrying a piece of clay marked with impenetrable symbols, which is nothing less than your death sentence.

Crushingly, the climax of the story is missing. We don’t know if Sargon bumped into a friendly scribe who read him the sentence, or if he had secretly learned to read cuneiform himself, or if Inanna stepped in again. Of all the partial tablets we’ve seen so far, this one is the one I’d be most excited to see turn up in some excavation or archive. My money is on Inanna.