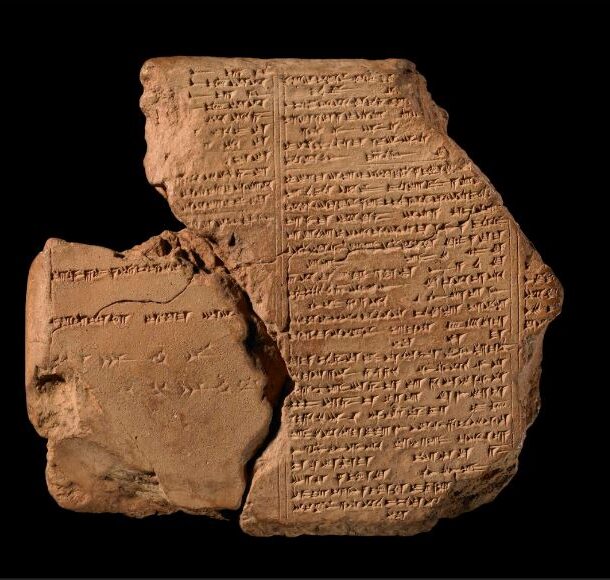

The Babylonian word inbu had a double meaning. Literally “fruit”, it could also allude to the act of sex. In today’s tablet, tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Inanna (called Ishtar in this Babylonian telling) asks the titular hero to give her his fruit, desiring sex with him. The first written example we know of someone with the urge to get fruity. So today’s topic is puns and double-entendres in Sumero-Akkadian.

People as a species tingle at uncertainty, we crave order and pattern, and are thrilled by a surprising resolution. A good joke plays on all these strings. In fact many human pastimes share this same characteristic – a build-up of tension, sustained uncertainty, and a release. The setup of a joke, the posing of a riddle, the thrill of flirtation, leading to satisfaction in the punchline, clever solution, or a roll in the hay. It’s addictive.

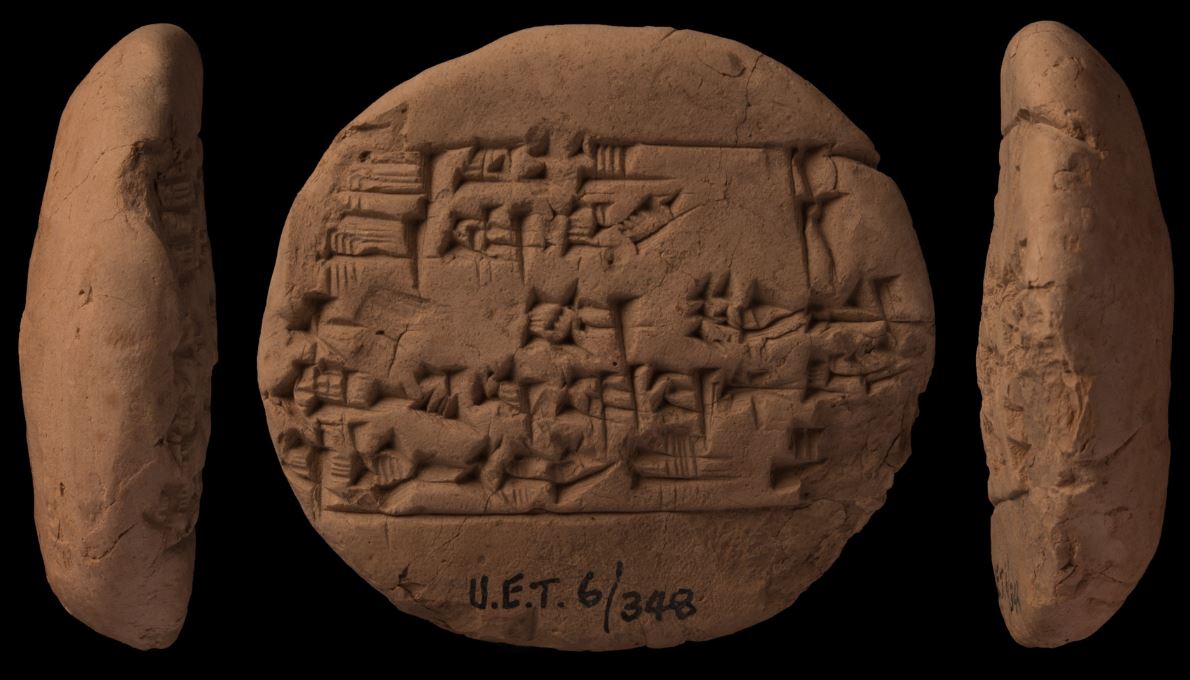

Sumerian logograms, which remained in use in Akkadian cuneiform, often had multiple meanings. The Sumerian sign UL, the equivalent of the Babylonian inbu, could also mean “distant time” and “to swell”. As well as such homonyms (same sign, same pronunciation, different meaning), heteronyms (same sign, different pronunciation, different meaning), and homophones (different sign, same pronunciation, different meaning) also abounded. There were at least five Sumerian logograms for “star”, which allowing for these three types of polysemy, variously meant things like “writing”, “to shine brightly”, “foundation”, “field”, and “wood wasp”, to name just a few. Part of the puzzle for scholars is in holding these multiple meanings in their minds as they read a text, until the uncertain possibilities condense into a single most probable interpretation.

If the logogram is a concept condensed into its essence, like Schrodinger’s famous cat in the box thought experiment, these puns ask us to accept multiple realities at once, with the promise of a later resolution when the box is opened.

To us, a pun is simple wordplay, worth nothing more than a chuckle or a groan. But according to Scott Noegel, cuneiform sources emphasise the idea that words were divine – a gift from the gods. Words, impressed on clay were as solid and real as the objects and concepts they encode. Puns and double meanings could be interpreted to reveal divine secrets. I came across this idea in a paper by John McHugh, whose doctoral dissertation argues that the story of the flood was encoded in the constellations visible in the skies of Sumer. The skies themselves serving as a kind of teleprompter for the storyteller. Notice that double meaning of the logogram for “star” and “writing”? The stories were written in the stars.

And to close on an aside, I recently read that Gilgamesh came in at number one in Cosmopolitan magazine’s 100 Hottest Heroes list. Why? Because women love a man in cuneiform.