I was struggling to come up with topics related to sound, then while looking at an image that looked different depending on which part you treated as negative space, it came to me. What about the absence of sound? Is there anything interesting to be said about deafness in ancient Mesopotamia? As it turns out, there is.

There are a couple of omens related to deaf people. According to one of the Summa Izbu omens, “If a woman of the palace gives birth to a deaf child – the possessions of the king will be lost”. In contrast, in the Summa Alu omens, “If deaf mean are numerous in a city, that city will be happy”.

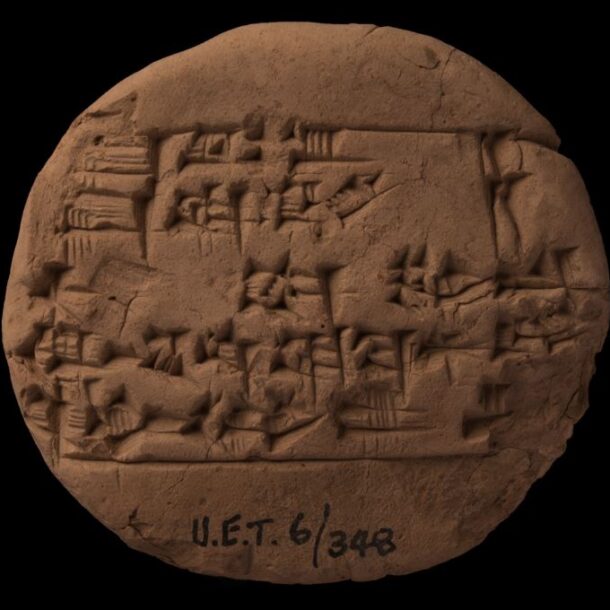

Today’s tablet of the day is another lentil, a school exercise containing the following riddle:

“A house that is open. A house that is closed. One looked at it but still it remained closed. Solution: One who is deaf.”

My interpretation of this is that the “house” is a mouth. It opens and closes in speech, but to a deaf person, even when it is open, it is as if it were closed. Nothing comes out; the speech is locked in.

Deafness is attested in Sumerian and Akkadian cuneiform sources both as a real condition, and as a metaphor. The word for deaf was also used as a synonym for stupid, so it’s unlikely that deaf people would have been taught to be scribes, especially as an important part of scribing was taking minutes and dictation. Given this, it must have been an awful experience to be deaf in those times. Locked in, and without sign language by which to communicate. However it may be that there was a chink to let the words out.

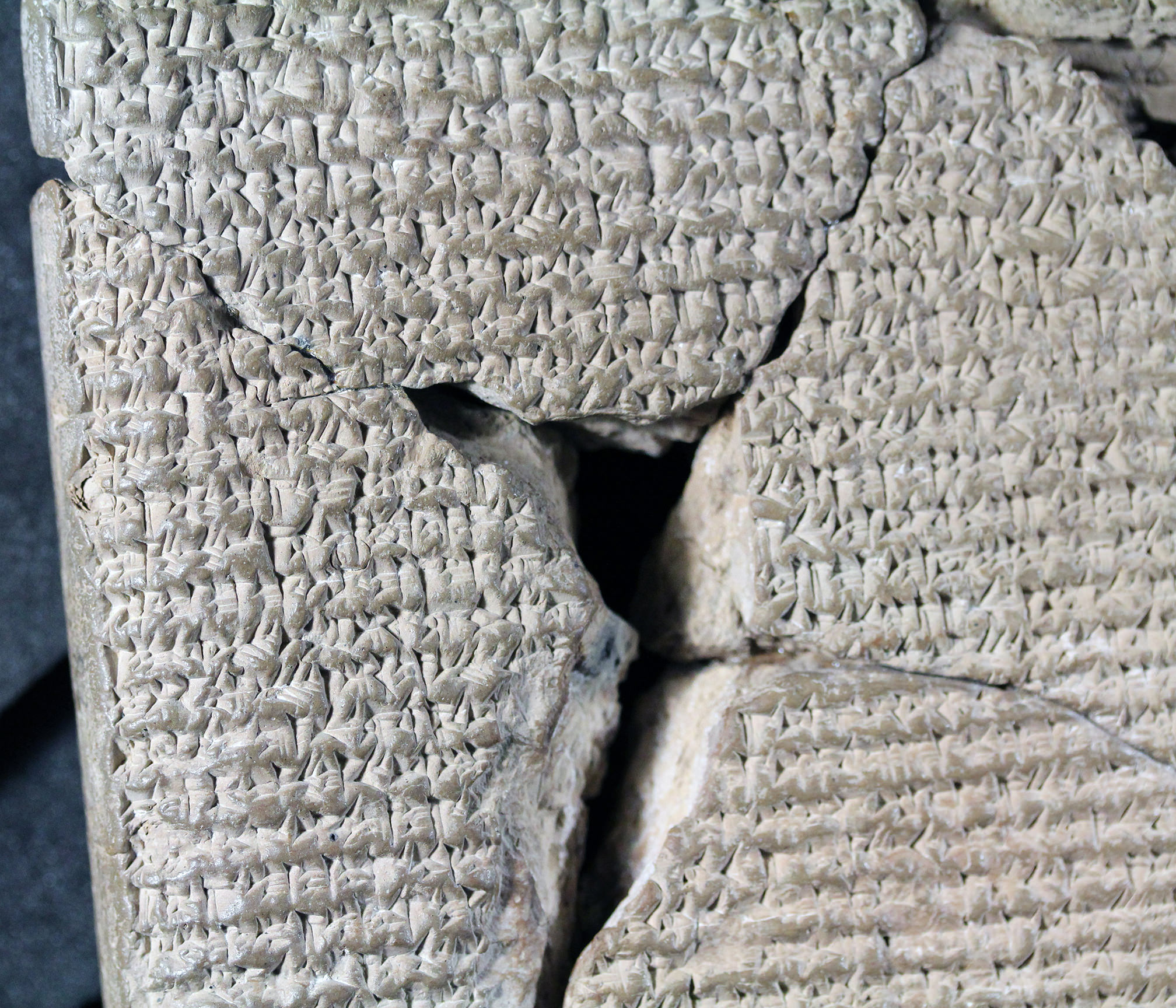

The Hittites were a contemporary culture of the Babylonians and Assyrians, frequently either warring or allied with them, and they also used a cuneiform script. They even used the same Sumerian sign for “deaf”. At their royal palace close to the modern-day village of Boghaskoy in central Turkey, there are a number of references to deaf servants, including a “chief deaf man”. To perform their duties, this team of deaf servants must have had a way to communicate with each other. It is known that when groups of deaf people spend time together, they have a natural tendency to develop sign languages, of a more elaborate nature than the simple signs that hearing people might use to communicate with them.

A relatively recent example of this comes from Nicaragua. Nicaraguan sign language is a language isolate, not genetically related (we’ll get to this on day 42) to other sign languages. It used to be that deaf people in Nicaragua were kept at home, isolated from other deaf people. This changed in 1981, when a school was opened in order to train them for work. It’s not clear why they weren’t taught a sign language, but as it turned out that wasn’t necessary. They began to develop a new language of their own, evolving compound signs to indicate grammatical concepts like verb tenses. Stephen Pinker argues that this process has a genetic basis – that we have an innate gift for language acquisition, a language gene – and that this Nicaraguan example is a chance to observe that gift in action.

Perhaps the Summa Alu omen may have been close to a point. If deaf people are numerous in a city, they have the chance to create a language among themselves, and so unlock the door to find happiness.