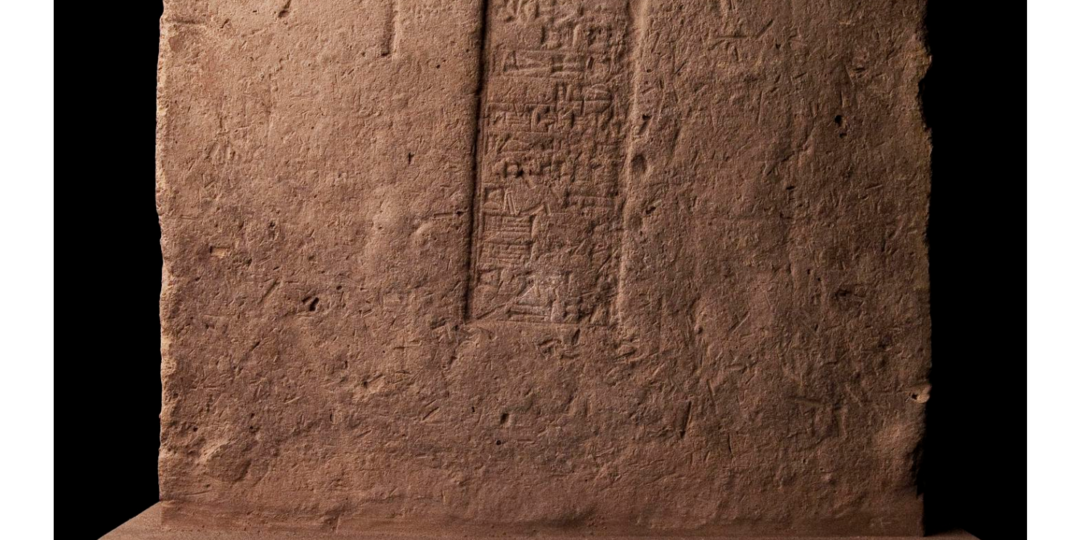

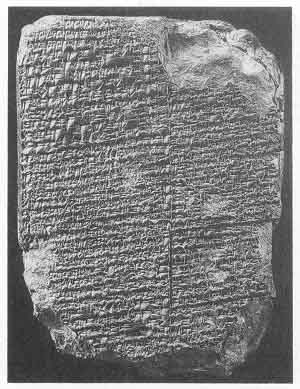

Cuneiform wasn’t always written directly onto clay tablets. Here we have characters stamped onto a brick in the temple of Shamash at Larsa.

Shamash was the Akkadian’s sun god, known earlier as Utu to the Sumerians. He was the twin brother of Inanna, the Queen of Heaven. He is one of the Mesopotamian gods with the longest tradition. He’s first heard of in around 3500 BC, 1300 years before this brick was laid in around 2200 BC, and was still being worshipped for another 1700 years.

The temple at Larsa was known as E-babbar (line 7 of the inscription), which is translated variously as the Shining House or the White House. There was another temple of the same name dedicated to him much further north at Sippar. Khammurabi, King of Babylon as the museum note calls him, is more commonly known these days as Hummarabi. He commissioned the building of this temple, “the temple E-babbar, his beloved temple, in Larsa, the city of his rule”, in order to associate his rule with Shamash. Shamash was a much-loved god, with a reputation for kindliness towards humans, as befits the warmth of the sun. He was also fair and saw the truth, as befits the light of the sun.

As is typical of sun gods from Utu to Helios to Sunna, Shamash left the gates of heaven each morning and travelled across the sky. In earlier times he did so on a boat or on horseback, but obviously did very well for himself. Later tradition has him well-attended by minor gods: two to open the gates for him to set off; the minor god Bunene was his charioteer across the skies; and even the sun chariot itself was referred to as a deity!

These shifting fortunes are surprising. What is it that makes the stories, names, genealogies, and relationships change? Why, once a story has been written down, does it continue to evolve? It’s tempting to think that the swirling silty waters of oral tradition might still, letting the clay settle out to the bottom, but this doesn’t seem to be the case. Perhaps this is a question of perspective. What appears like a lot of change from our viewing point five millennia later perhaps isn’t so great when seen on the order of centuries.

It’s a slow accretion of layers of sediment, laid down with each flood, subtly changing the landscape with each passing year, but the changes noticed only when we look back at the procession of moments captured in the kilns.