Nabonidus, the final native-born ruler of Assyria, made a statue-related political misstep. In Mesopotamia, each city had their own god, who protected them, and at whose pleasure the local ruler ruled. There was a tradition of conquering armies to steal the statues that literally embodied them – “carrying off their kingship”, in the phrase we saw on day 25. In 539 BC or a little before, Nabonidus tried to prevent Cyrus the Great, king of the Achaemenid Empire, from doing just that, by gathering up the regional gods and bringing them to the fortified city of Babylon.

This had been tried before, successfully, by Nabopolassar in 625 BC against the incursions of the Assyrians. The problem is, Nabonidus gambled and lost.

In a classic example of history being written by the victors, Cyrus the Great’s propaganda machine painted his win as force for restoration – for returning the gods to their rightful places and fixing all that ailed the Assyrians. Asking in return, only that Babylonia should become a part of his empire.

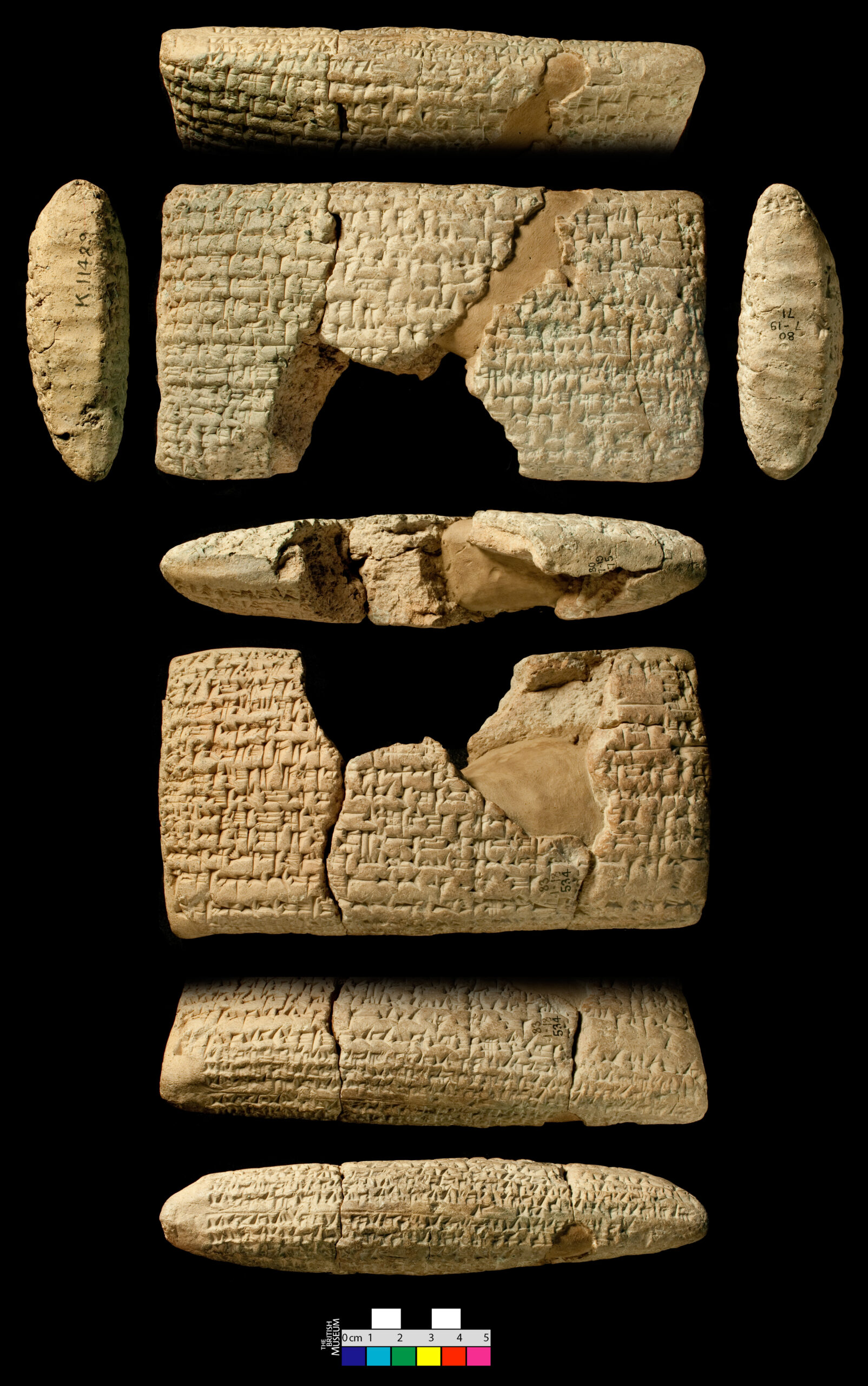

We’re straying from the path of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform here; Old Persian had its own style of cuneiform. There is some debate as to when, but what is known is that rather than being a natural development from pictograms into simplified and abstracted logograms and eventually a phonetic alphabet, Old Persian cuneiform was born fully-fledged with 36 phonetic characters and just 8 logograms. The debate is only over whether this happened under Cyrus the Great, or under Darius the Great who succeeded him. What we do know is that the oldest extant example of Old Persian script was created in the reign of Darius, and it is one of the most important discoveries for the decipherment of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform.

Today we’re truly stretching the definition of “tablet”. The Behistun Inscription stands at 1300 meters on a mountainside in modern-day Iran, Mount Behistun. The monument is 15 metres high by 25 meters wide, and requires 100 metres of rock climb to reach from the road. And here’s the important part: it’s trilingual, carved three similar scripts – Old Persian, Elamite, and the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian – a Rosetta Stone for cuneiform.

The Old Persian part of the inscription was first copied and brought to Europe by Carsten Niebuhr in the 1760s and was published in 1778. Though surely not the easiest of tasks, it did yield up some secrets to the decipherment efforts of one Sir Henry Rawlinson (among others). The key was in his intuition that some of the characters seemed to repeat, and that led to a moment of inspiration. What kind of thing would be expected at the start of such a monumental piece of writing? Was this perhaps a genealogy of its creator? And so this repeated word, could it be “king”?

“I am Darius, the great king, the king of kings, the king in Persia, the king of countries, the son of Hystaspes, the grandson of Arsames, the Achaemenide…”, it began, linking Darius back to his common ancestor with Cyrus the Great. Before continuing for another 4000 words of battles, slayings, subjugations and conquests. King Darius had a lot to say for himself, though it wouldn’t be fully translated for some time to come.

This decipherment inroad into the Old Persian was made before other two texts had even been copied and brought down from the mountain. It would take Rawlinson’s heroic, Indiana Jones-like, efforts to move our story along. He visited the site on two occasions and, with the help of local boys and some serious mountain-climbing prowess, first transcribed the Old Persian, and later the much more inaccessible Elamite and Babylonian, taking papier-mâché casts of the characters. Back in Europe, Rawlinson would eventually be credited with decipherment of the Akkadian cuneiform.

Like overlapping sequences of tree rings, this trilingual inscription, along with many bilingual and multilingual documents and tablets allow us to track back from Middle Persian to Old Persian, from Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian, and finally to Akkadian and Sumerian. And in finer detail, the many varieties and dialects of Akkadian and Sumerian are also decipherable to those with the patience, dedication, and the right flash of inspiration. While Rawlinson played a role, undeniably, the are more members of the cast in this story.

But they will have to wait. The next seven days we’re going to spend feasting on bread and wine, beer and cheese, and other products of fermentation in the ancient world.