Ok, we made it to week three and the lockdown is starting to ease here in Barcelona. Since the clapping has also stopped, I’m thinking it’s a fine time to thanks to our medical professionals with a week of posts about Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform tablets on a medical theme.

In Sumerian times, the medical profession was divided into two branches. The asu, and the asipu. Asu carried out therapeutic medicine – undertaking surgery and prescribing pharmaceutical or herbal prescriptions in something we would recognise as medicine. Asipu on the other hand were concerned with religious medicine – closer to exorcists in function than a modern medical practitioner. In fact, their main instructional text is known as the Exorcists Manual. We could term their art apotropaic magic, which is to say magic healing, intended to ward off evil in its many forms – up to and including natural disasters, something that is manifestly absent from the curriculum in modern medical schools.

That’s not to say that what the asipu concerned themselves with was useless. M.J. Geller points out that what they practiced was a rudimentary form of psychotherapy, concerned as it was with treating those feeling affected by “‘evil spells’, ‘evil curses’, ‘witchcraft’, ‘[and] the (effects) of an oath’”, all of which we might now see as manifestations of anxiety, paranoia, or other neuroses. The incantations and cleansing rituals described in the Exorcists Manual were intended to unburden the patient from their fear and guilt. Inasmuch as “complementary medicine” works in providing relief, it is likely through a similar mechanism to that of the asipu.

One of the types of visitation treated by the asipu was from the sexy ghost Lilith, and her male counterpart Lilu who would attempt to make sweety demon love to their human objects of desire while they slept. The visitations of incubi and succubi have been a perennial “torment” of humanity, perhaps as a means of explaining wet dreams without implying any desire on the part of the dreamer. The treatment, somewhat hilariously, was to conduct a ritual marriage between figurines representing the patient and the sexy ghost, like some sort of sacred Barbie and Ken.

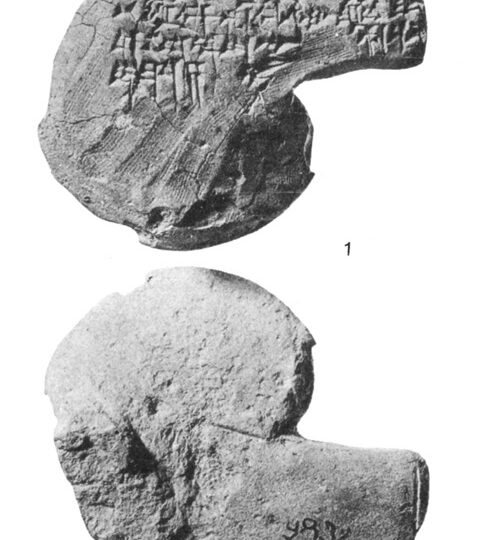

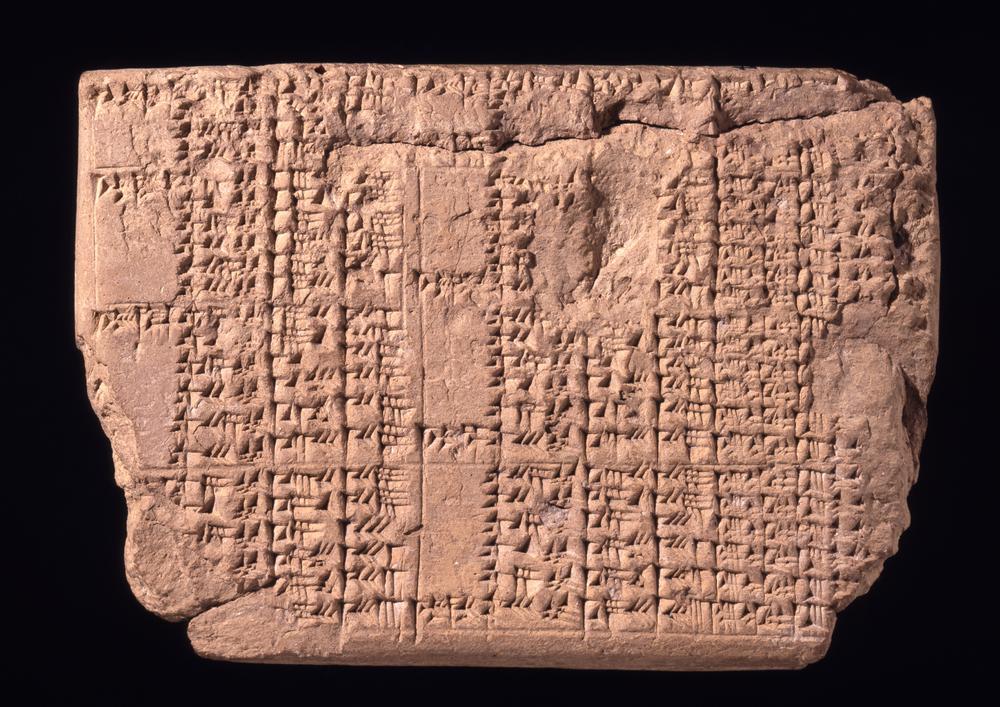

The profession of asipu overlaps not only with that of the asu, but also with that of the baru. This advanced part of their curriculum covered divination from the stars (astrology) and the entrails, particularly livers, of animals (known as extispicy in the general case, and hepascopy in the particular case of the liver). Today’s tablet is a clay model of a liver, used for instruction in interpreting signs on the real thing. In later texts, the liver was referred to as the Tablet of the Gods, upon which their judgements could be read. Their judgements though, were not particularly profound or detailed. The asipu would pose a question and the answer would be revealed on the liver of a sacrificial sheep as positive, negative, or uncertain. Yes, like a magic 8-ball. Enough for today. We’ll pick up tomorrow with a focus on the “real medicine” of the asu.