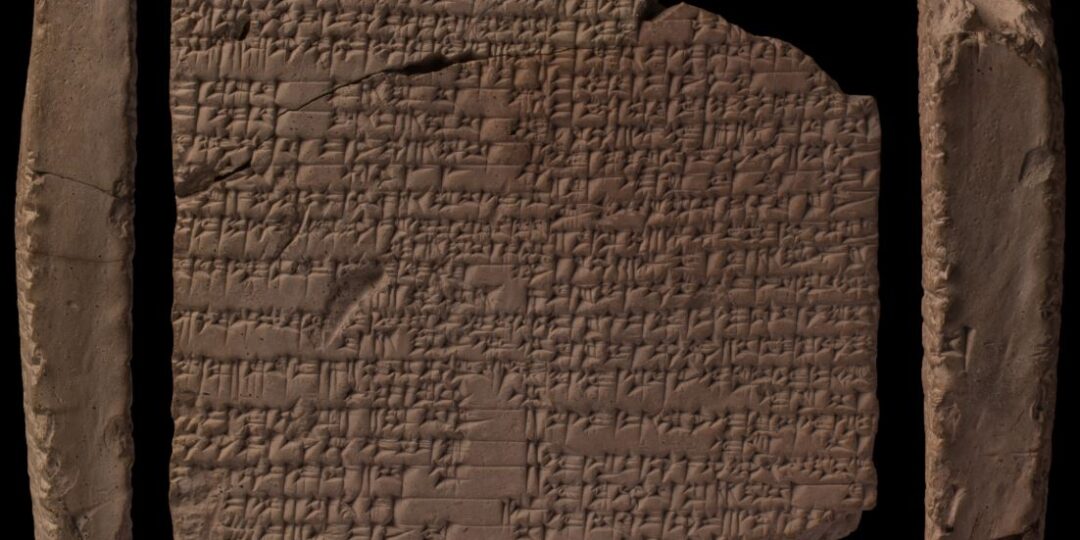

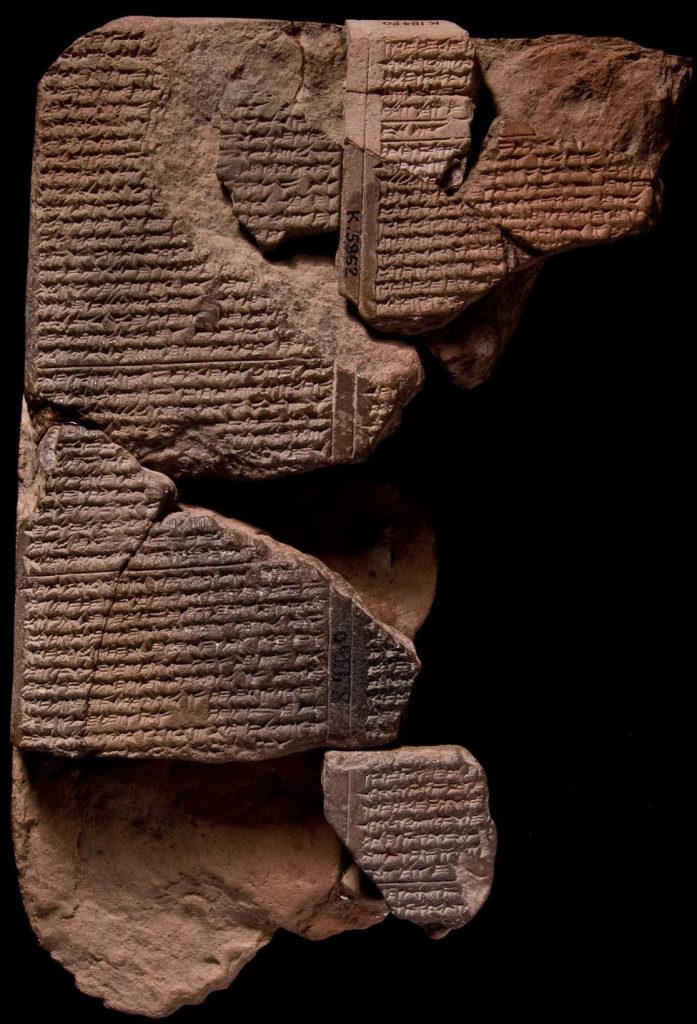

The Sumerian Farmer’s Almanac was discovered in 1949 on an expedition joint-sponsored by the University of Chicago and the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. In “History Begins at Sumer”, Samuel Noah Kramer describes the poor condition of the 3 x 4 ½ inch tablet upon its arrival in Pennsylvania. He drops a few intriguing hints about the process of conservation (baking, cleaning, mending) through which almost the entire text became legible.

The name “Mesopotamia” little translates to “the land between rivers”. It was a rich, fertile land, due to the regular flooding from the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. The almanac describes how this natural process was harnessed through earthworks, used to control flooding several times throughout the farmer’s year. The fields were flooded, ploughed, tilled, seeded, and flooded again a second, third and possibly fourth time before harvest.

A line in the almanac, “After working the field (with) the bardili plough by means of the force of one seed plough”, refers to a fascinatingly advanced invention used in the fields. The seed plough, developed in Sumeria in around 2300 BC, was based on a regular plough. It consisted of a stone plough-share attached to a wooden shaft, pulled by one or more oxen, with the addition of a funnel containing seeds which would be scattered in the furrow behind the plough.

In reading about the almanac, I found a link to Hesiod’s Works and Days – then the oldest known description of farming, though it is almost a thousand years more recent than the Farmer’s Almanac. Hesiod’s work contains much mythological content, talk of the Golden Age, and advice for living a good life in the society of the time. Reading it this morning it conjured up the image of Polonius instructing Laertes and Ophelia in Hamlet, a string of sententious platitudes intended as fatherly (or elder-brotherly in the case of Hesiod to Perses) advice.

The Sumerian Farmer’s Almanac by contrast is a nuts-and-bolts, somewhat dry, description of ploughs and farmhands, measurements and procedures. Little if any of the author’s living voice comes through.

So far, I have the impression that much of the extant Sumerian literature has this character. There are, it must be said, a few possible explanations for that impression which are worth bearing in mind. First and simplest, it may be an artifact of this week’s focus on inventions and instruction manuals. Second, it may relate to the translation. Much if not all of the of the ancient Greek I’ve read in translation has been of literary character, and has perhaps stayed less faithful to the original text in order to render a better take on the subtleties of language; my primary sources for Sumerian translations have been ETCSL and CDLI – dryer, more academic, full of explanations of uncertain words and ellipses for missing fragments of text. Third, we perhaps understand the subtleties of Ancient Greek vocabulary better than those of the various Sumerian languages. In many cases, a word is known from a single instance in the record, and so the connotations which might be recoverable from seeing it in multiple contexts are not (yet) available to us.

Tomorrow we turn back to a more mythological take on agricultural inventions, so we can make a comparison.