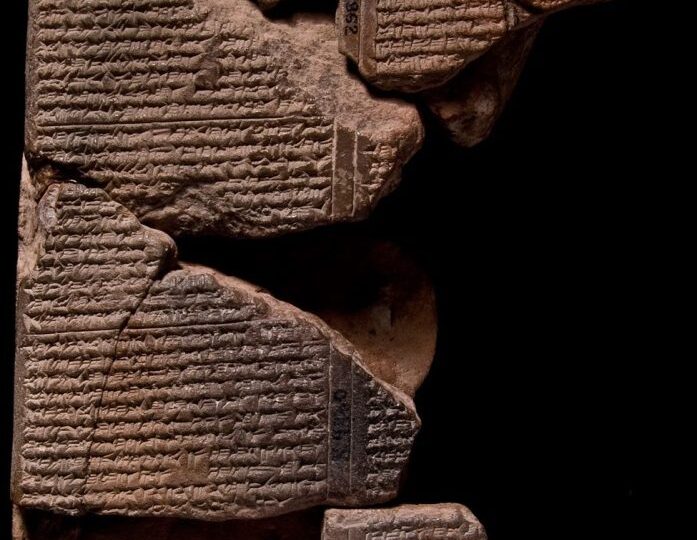

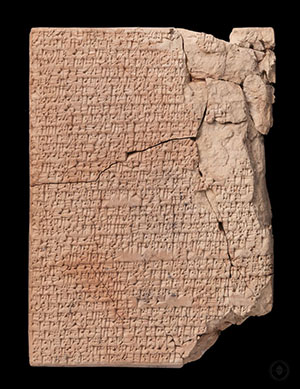

As those of you who are paying attention will have seen mentioned a couple of days ago, the Sumerians developed kilns, not for baking cuneiform tablets, but for producing pottery. They also put kilns to a couple of other major uses: mass-producing bricks for building, and glassmaking. The tablet we’re looking at today is one of three in the British Museum and instructs on the building of a glassmaking kiln and how to use one to produce coloured glass.

What is quite fantastic is that this record, which I think it is fair to call an ancient tablet, contains what the scribe at the time called a “copy of an [ancient tablet]”. These procedures had already been fixed from a time before contemporary living memory, the research and experimentation immortalised in impressions on clay like the footprints of those who walked this path before.

The recipes here are significantly more detailed than in the cookery book yesterday: making stew is more forgiving than making glass, and so precise details of ingredients and temperature are not critical. The glassmaking recipes on the other hand list every step from the astrological search for a propitious day in a favourable month to begin the construction, through the sacrifice of a sheep in the presence of Kubu demons, to the pouring of honey over burning juniper – before even dreaming of lighting the fire in the kiln. Then several combination of ingredients are listed, for the creation of different types of coloured glass – “slow copper”, “quru-wood”, “salicornia” – the list is “not missing even a single hair of barley”, in the idiomatic expression the scribe used to warn that the instructions are to be followed precisely. Details of the colours the molten glass must be seen to change to are given. For some steps it must glow red, or yellow, or even green before it’s allowed to cool and crystallise.

As I’ve been writing about cuneiform, the phrase “crystallisation of thought” keeps popping into my mind as description of the transformation that happens during the act of writing down an idea. There’s no more appropriate place to roll it out that a post on glassmaking. The recipes on today’s tablet are a solidified record of the thoughts of experts, trying first one thing then another, and finally landing on the right combination of minerals, fuel, time, and temperature to make something magical in the kiln.

Access to such expert knowledge is something we take for granted nowadays. Entire industries are built to support the dissemination of the latest thoughts. Power stations burn, wind turbines spin, sunlight is captured and forced down wires to power the search engines and web browsers that allow information to keep flowing. In the time before writing, the world was a different place. Knowledge had to pass from mouth to ear. It had to be stored in fallible memory. In terms of revolutions in human development, nothing comes close to the leap forward enabled by this transmutation of abstract thoughts into solid matter.