There are essentially two types of job. In one you sell your products. This is the route of the artisan and the farmer, where you sell goods that you have produced in return for goods or money of equivalent value. In the other you sell your labour in return for a wage. We’ll ignore middlemen, providers of capital, and so on for now. We’ll get onto that in week 12 on the economics of cuneiform culture. For now, we just need to think about goods and labour.

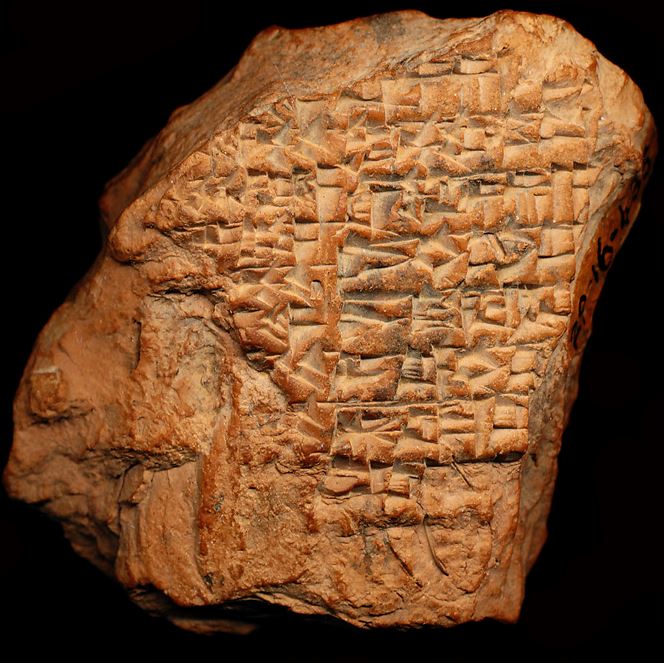

In Mesopotamian administrative bookkeeping… Hey, where are you going? Come back, this is exciting. Interesting at least? Still with me? Ok, so along with their invention of jobs, the Mesopotamians were outstanding bookkeepers, tracking in great detail the floods of grain and other produce flowing in and out of the city’s stores. These bean-counters needed to invent timekeeping to calculate wages. There’s no wage-work without clock-watching. And “watching” is precisely the word we need.

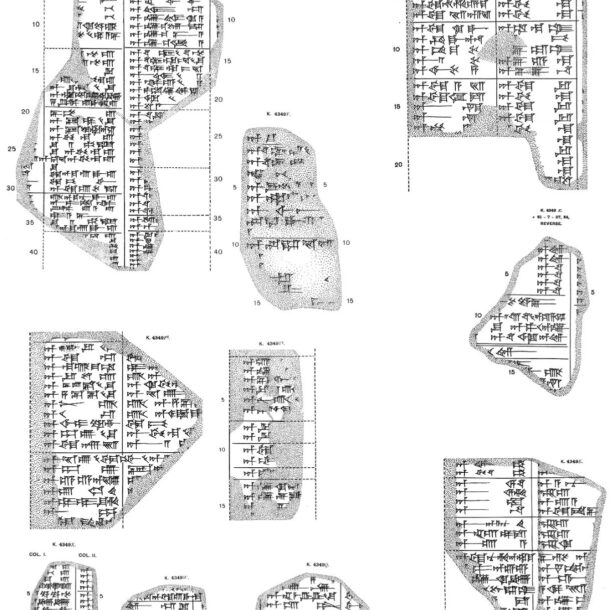

For today’s job, we’re looking at watchmen. Coming up to harvest time, fields and orchards were full of valuable produce which might be stolen. And even at other times of the year, wild animals needed to be kept off the crops. Watchmen would be posted to keep an eye on things in the fields. In the streets of the cities they also had a watch. These city watchmen were more like a member of the Ankh Morpork Watch. Like Sam Vimes or Constable Carrot, something akin to a policeman. Their mythological counterpart and patron was Ḫendursanga. Like his pastoral equivalent Dumuzi the shepherd, Ḫendursanga was a god of protection in the cities. He patrolled the streets at night, lighting them with a torch and discouraging ne’er-do-wells. The real night watchmen would invoke his name when they lit their own torches and set out on their rounds. Today’s image is a hand-drawn copy of tablet VI of the gods list, An = Anum, a Middle-Babylonian compilation of hundreds of Sumerian gods and their Akkadian equivalents. It includes the name Ḫendursanga in Sumerian, and his Akkadian name Išum.

The workday, and worknight were each divided into three watches. Ḫendursanga’s earthly colleagues worked their nights in three night-watches, each of nominally four hours. But given that day and night were divided by sunrise and sunset, these obviously fluctuated with the seasons. A night-watch in winter was paid more than one in summer.

This morning I’ve been mostly struggling to find the source in which I first saw this calculation of the relative measures of grain doled out in return for summer and winter watches. I know it’s out there but I’ve had no success. No matter. Something in that document made me take note of the concept that a measure of time had it’s equivalent as a weight of barley or wheat. Like T.S. Eliot’s evenings, mornings, afternoons measured out with coffee-spoons, the watchmen’s nights were measured out in grain-bowls. That’s an hourly wage by another name; an exchange of goods for time, not for of goods for other goods of the same value. This direct conversion from time to reward, this commodification of time, was the first step towards today’s nine-to-five.