Far more beginnings of apprentice copies of Gilgamesh survive than middles and ends. The source where I read this fact suggested it implies a high drop-out rate for scribe school. A more charitable interpretation would be that it was perfectly possible to earn a living as a scribe without having copied the entirety of this epic.

Dick Guindon, a syndicated cartoonist out of Minnesota once uttered the phrase:

“Writing is nature’s way of letting you know how sloppy your thinking is.”

He’ll get no argument from me on that. Every day as I sit down to write, usually after lying in bed waiting for the alarm and thinking through my profound influence for the day, I realise that what I’d been planning just doesn’t make sense once I try putting it into words. At least I have the luxury of a word processor. Pity the poor scribe who sets out at his or her tablet, halfway down runs out of steam, and has to slap the clay back to a smooth tabula rasa. Must have been cathartic though.

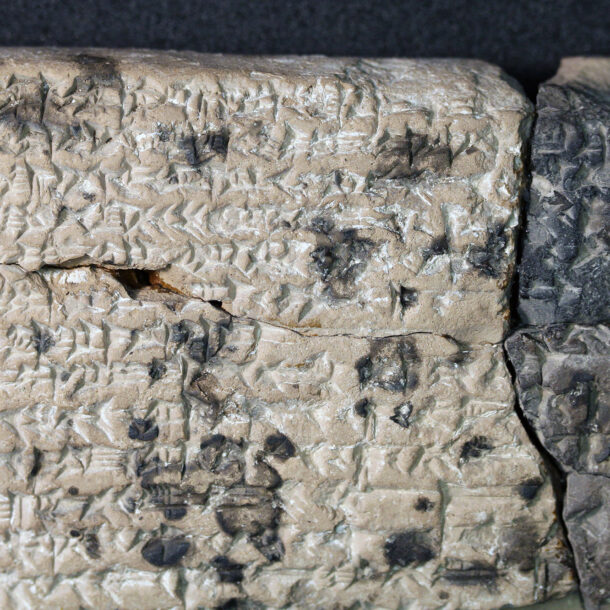

One of the things that fascinates me about studying cuneiform tablets is that we see individuals. Not just royalty and priests, but the scribes who wrote about them. Scribes would generally attach a colophon identifying themselves to their tablet, at least the important ones, these don’t always survive. But there are other ways of piercing the fog of time and assigning authorship.

First, we have their handwriting. Each scribe had a particular set of tics and characteristic forms, such as the scribe of today’s tablet’s quadrangular ŠÀ sign. The tablet is a compilation of creative “etymologies” for names of gods and goddesses, another example of the importance of puns and wordplay. A cute example of this from another tablet is the pseudo-etymology of the word ḫurdatu meaning “vulva” explained as ḫurri dādi, “cavity of the darling”, where “darling” is taken to mean “son”. This kind of thinking, etymology by coincidence, has nowadays mostly been supplanted by a more critical approach, but hangs on in conspiracy theory circles, along with its close companion numerology.

Secondly, we have stylistic analysis of the text. This week I stumbled across an article by George Orwell from the final year of World War II in which he writes:

“The Gestapo is said to have teams of literary critics whose job is to determine, by means of stylistic comparison, the authorship of anonymous pamphlets. I have always thought that, if only it were in a better cause, this is exactly the job I would like to have.”

As with the Gestapo, scholars of Shakespeare use this kind of analysis to try and attribute his works, or parts of them, to other playwrights, or to confirm them as the bard’s own. And in a forensic setting, James R. Fitzgerald’s linguistic analysis was instrumental in catching the Unabomber.

Finally, and to me most beautifully, many a tablet is so well preserved that we can see the scribe’s fingerprints where they held the clay as they wrote. Sure, we can’t see the whorls and loops, but the size of the fingertips, idiosyncrasies of grip and so on can be enough to suggest that two tablets are from the same hand.

There are countless people out there today, myself included, who didn’t make it through their doctorate, but went on to find employment using the skills they learned, and had a lot of fun learning along the way. In the same way, I can’t imagine that a scribe, sufficiently skilled to copy out the start of the Epic of Gilgamesh, would fail to find a use for their literacy. It’s not always necessary to complete a project for it to teach you something, and you don’t have to be great, or even particularly good at something to enjoy getting better at it. Draw, paint, cook, sing, study, write, all just for the joy of it. If it pleases other people, that’s great too, but do it either way. Do it for yourself.