Say what you like about Herodotus, he knows how to tell a memorable story. Dan Carlin in his Hardcore History podcast likes to talk about how before the Greeks came along, history was in black and white. Previous writers would chronicle without characterisation. Catalogue without colour. They would tell bare facts with no story to draw the reader along. Then Herodotus comes along to colourise the scene. He may have tended to lean on the colour at the expense of the facts, but why do you think we keep coming back to him? As the old newspaper adage goes, don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story.

This week we’re looking at professions, starting with “the oldest profession in the world” and the creation of the patriarchy. The Book of Revelation makes much of “the Whore of Babylon”, dressed in purple and scarlet, her cup “full of abominations and filthiness of her fornication”. Here’s what Herodotus has to tell us about ritual prostitution in Babylon:

“The foulest Babylonian custom is that which compels every woman of the land to sit in the temple of Aphrodite and have intercourse with some stranger at least once in her life. Once a woman has taken her place there, she does not go away to her home before some stranger has cast money into her lap, and had intercourse with her. […] It does not matter what sum the money is; the woman will never refuse, for that would be a sin. […] So then the women that are fair and tall are soon free to depart, but the uncomely have long to wait.”

As usual, we have only the colourful Greek’s word to go on for this practice. We do know that ritual prostitution associated with the temples was commonplace, but here Herodotus seems to have touched up his story, telling the best version he’d been told rather than the most reliable.

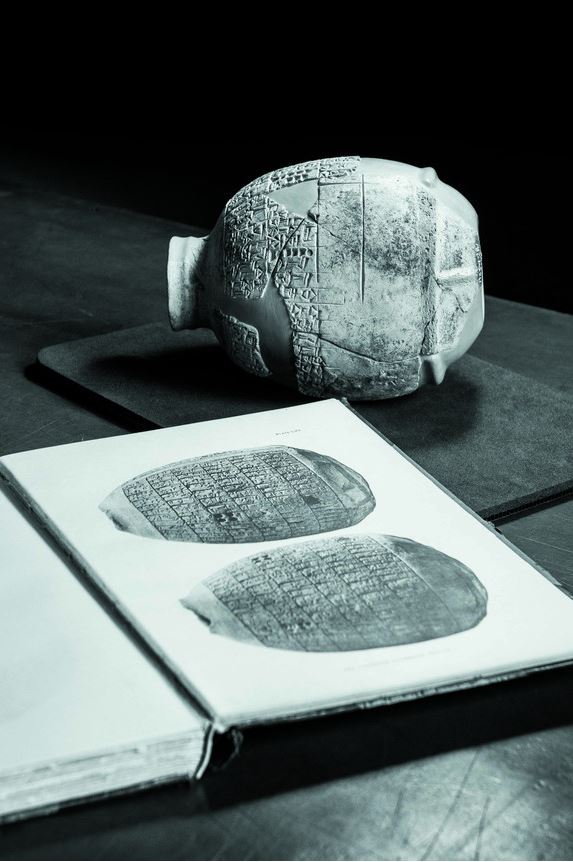

While it may not be the oldest profession, sex work is at least one of them. It appears on the earliest Sumerian list of professions (there’ll be more on this all week), as well as on a record of wages of grain from the Early Dynastic period. In his analysis of this accounting tablet (our tablet of the day today), Jerald Star tells us the names of six of the women, one of whom seems to have blagged a double ration. He also writes critically of the sex workers status as outsiders, lowly members of society. In this he doesn’t appear to recognise that we can’t really see the role of sex work and sex workers in Sumer, and in fact he neglects the evidence that it could be if not respectable, at least no more disreputable than a tavern keeper. A temple prostitute (harimtu) even tames Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh (day 115), playing a major role in the story of the birth of civilisation. There was though, a distinction between religious prostitution attached to the temple and street prostitution out by the town wall, with purveyors of the latter more at risk from their drunken clients.

By the time of the Assyrians however, the veil is quite literally lifted and there is no longer any uncertainty about the place of women who sell sex. The Middle-Assyrian Law 40 regulates who may and may not wear a veil, and prostitutes are firmly in the class who may not. In mandating clothing for women based on their hierarchy (first wife, concubine, girlfriend, one the wife is jealous of, etc), and in explicitly linking that hierarchy to these women’s sexual relationship to men, we see an explicit symbol of patriarchal control which lingers on in pink dresses as a bonny daughter, white dress as blushing bride, right through to the black of her widow’s weeds. Each stage in a woman’s life identified with her relationship to a man, and outwardly marked for all to see.