After yesterday’s brief foray north to Mari, we’re finishing back in Sumer proper, with the city state of Umma. As with Ur, the first description of the site in modern times, as well as an illustration of what he called the Ruins of Hammám, come from the pen of William Loftus. He writes:

“The hazy atmosphere of early morning is peculiarly favourable to considerations and impressions of [the gradual rise and rapid fall of these sites], and the gray mist intervening between the gazer and the object of his reflections, imparts to it a dreamy existence.”

As I copy out these words early in the morning, I can picture myself approaching the object of Loftus’s drawing and their strange mushroom-like forms.

Only now the haze begins to clear, and I see the footnote on page 116 which reveals that this isn’t Umma after all, but another nearby site. The diorite statue Loftus describes finding at the Ruins of Hammám is not the same as the smaller one he found at Tell Jokha. In fact, this single brief footnote is Loftus’s only mention of Umma that I’ve been able to turn up.

If there’s one thing I’m getting used to in this project, it’s finding myself off the path and wandering in the wilderness. But it’s not just me who has to constantly embrace the idea of being mistaken. This process of reappraisal, reattribution, and renaming is bread and milk to archaeologists. I was trying to track down Tell Jokha in Loftus’s snappily-titled “Travels and researches in Chaldaea and Susiana with an account of excavations at Warka, the Erech of Nimrod, and Shush, Shushan the Palace of Esther, in 1849-52”, but it’s also been suggested that Umma was to be found some 7 km away from Jokha at Umm al-Aqarib. The currently popular theory, based on textual and archival analysis, is that Umma was actually a twin city comprising both Umm al-Aqarib and Jokha.

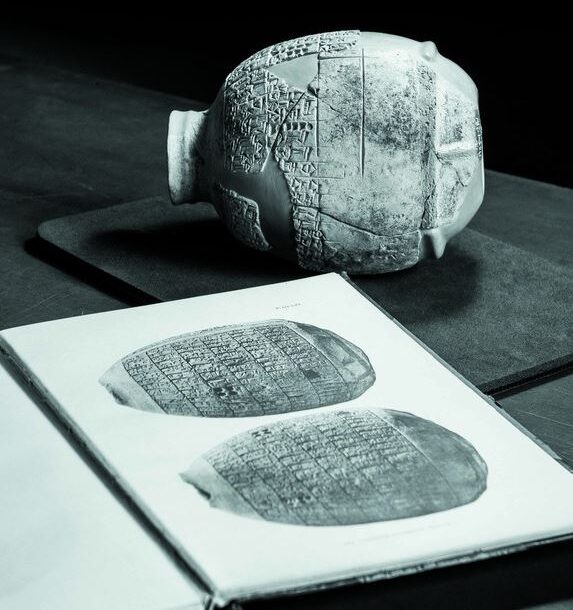

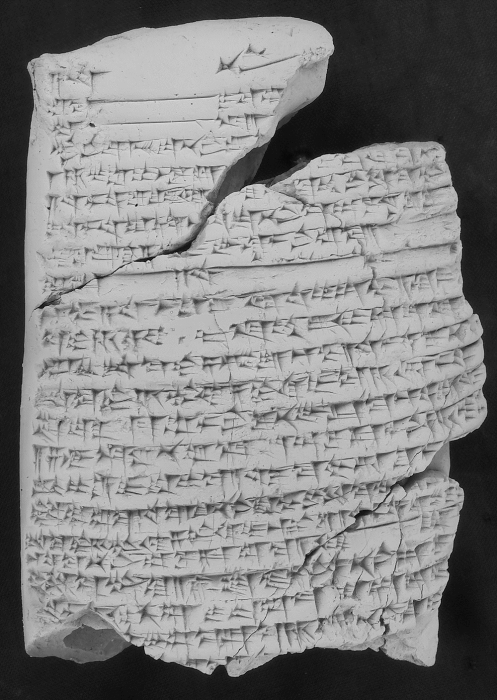

The city god of Umma was Shara, son of Inanna, described as a minor god of war. Though from Inanna’s own words in her Descent to the Netherworld, “Shara is my singer, my manicurist and my hairdresser. How could I turn him over to you?”, it seems that was just one of his many talents. He features heavily in today’s cuneiform inscription, which is on a terracotta object known as the “Vase of King Gishakidu”. The inscription redefines the border of Umma with Lagash, long the source of disputes between the two kingdoms as we saw on day 24. In yet another reappraisal, researchers at the British Museum realised that the object had always been displayed the wrong way up. What had long been considered to be a vase is in fact a ceremonial mace-head.

Keen amateurs like myself, and experts alike are prone to make mistakes, though mine are surely more blundering and less informed. In this game of Assyriology things are rarely what they appear at first glance. It’s a clichéd metaphor to talk about mirages in the desert, shifting sands, and the wandering silty tributaries of the marshlands, but they are apposite. On such uncertain footings missteps will be made. The key is to recognise and own them.