Today and tomorrow we’re looking at quasi-historical royalty; more legend than real, like England’s King Arthur or Queen Leda of Sparta. Today’s legendary king is Etana of Kish, and tomorrow our queen will be Semiramis of Babylon.

Etana king of Kish, according to the Sumerian Kings List, reigned sometime in the 3rd millennium BC. He’s most famous for the Myth of Etana, the story of how he came to have an heir. It’s a convoluted and magical story, including talking snake and a talking eagle who fall out when the eagle eats the snake’s children, even though he’s promised not to. The eagle is punished by having his wing and tail feathers cut off and is thrown into a pit. Meanwhile, Etana and his wife are trying and praying for an heir, but it’s not happening for them. Luckily for both the eagle and for Etana and family, Shamash (day 4) decides to intervene by sending Etana to help the eagle back to health. In return, the eagle interprets Etana’s dreams about visiting Ishtar, the Babylonian name for Inanna (pick a day, you’ll probably find her), in heaven where she gave him the Plant of Birth. After a couple of tries, the eagle and Etana fly up to the heavens and (presumably – this bit is missing) make the dream come true. On their return, Etana and his wife produce the heir they’d been praying for.

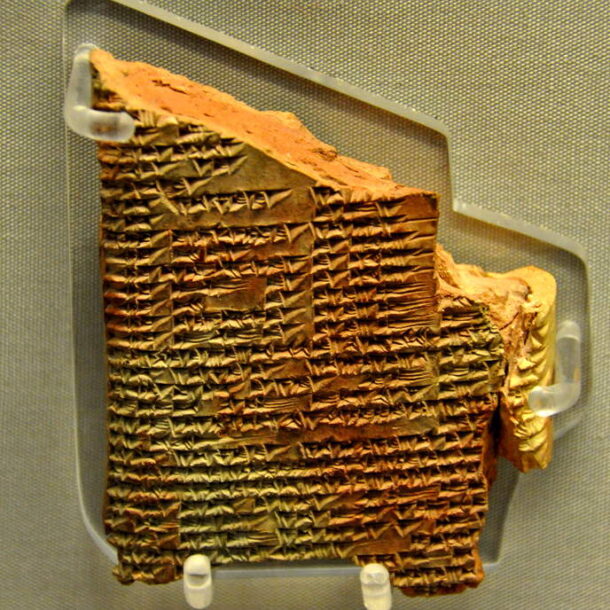

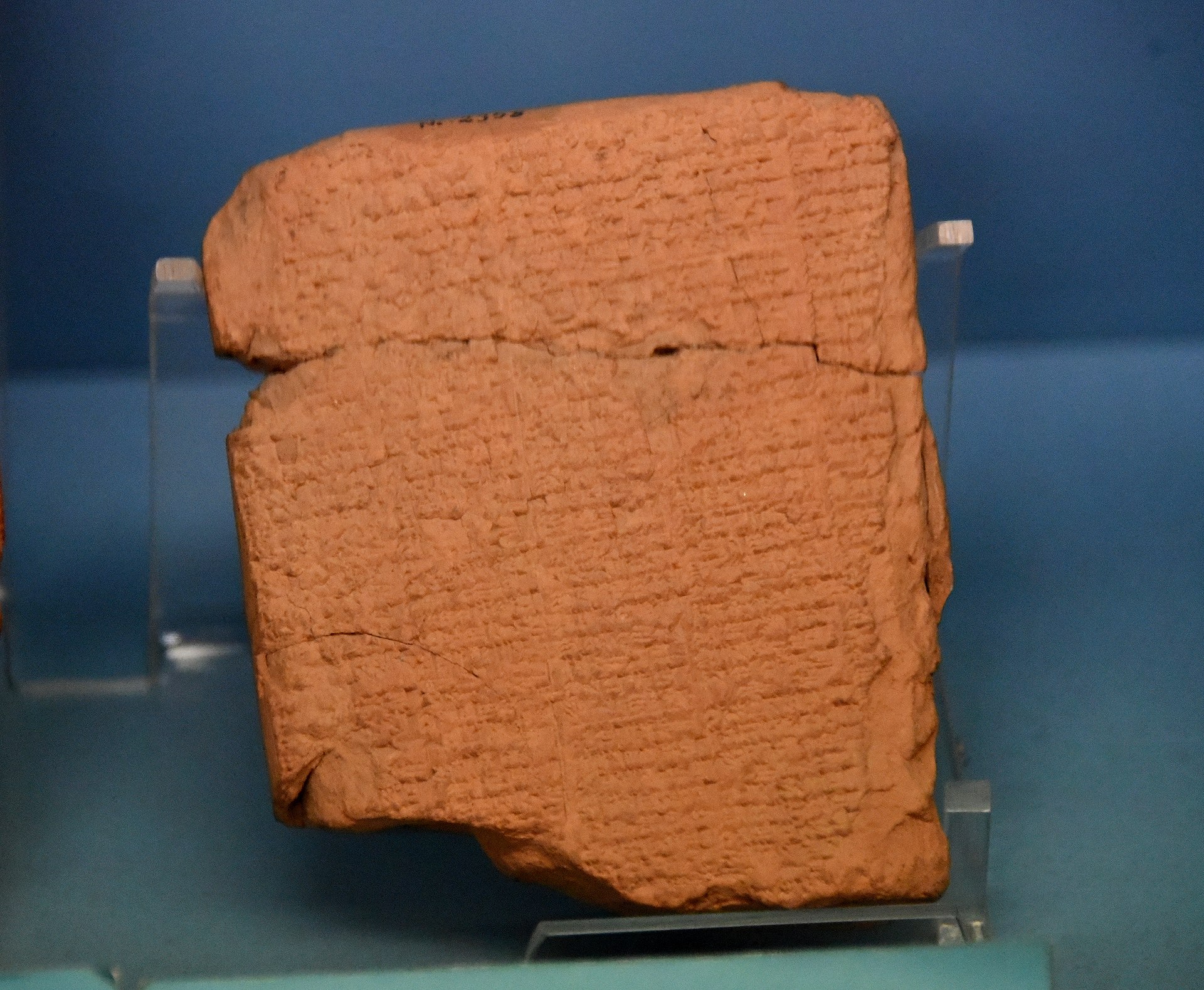

There are several partial versions of this myth. Imagery of Etana on the back of an eagle exists from the time of Sargon the Great (2334 – 2284 BC, and day 44), and the most recent known fragment is today’s tablet from Ashurbanipal’s library in the 7th century BC (more on that on day 49). That’s a story retold for 1500 years as a minimum, and other tablets from the intervening centuries are consistent copies.

This is because writing down an idea is like freezing sperm or an egg, or saving a seed. Someone can come along later and your idea can germinate in their mind. They can evolve it, combine it with their own ideas, and pass it on. That the thoughts of people from 5000 years ago have made it across such a chasm of time to us is one of those humbling realisations, like staring into the night sky and grasping at infinity. All thanks to the invention of writing.

But where and how you write makes a difference. In the latter days of cuneiform culture, during the Hellenistic period after Alexander the Great’s arrival in Babylon in 331 BC, writing cuneiform on clay had been almost totally supplanted by writing on papyrus, or possibly leather. But if the scribes working with the newfangled technology thought that their Aramaic and Greek words would ring down through the ages, they were sorely mistaken. Not a single document remains from that period.

What about our current writing methods? Are they as doomed to being lost as those Hellenistic writings? I imagine the terabytes, petabytes, exabytes of data that Facebook and WordPress store will one day be deleted, the servers powered down and recycled or tossed into landfill. Like frozen sperm or eggs when the freezer goes off. Books printed on paper will fare better – more like seeds – but those too will lose the spark of life if we’re thinking on the scale of millennia.

So what’s the alternative? I dread to think how many clay tablets would be needed to hold even the contents of my current challenge. Someone has estimated the information density of cuneiform as around 2000 words per kg of clay. If the approximately 24,000 words of this project so far were to be transcribed onto cuneiform tablets, they would weigh in the region of 12 kilos. By the time we’re done, it would be around 50 kilos. And that’s without the pictures.

No. I probably need to come to terms with the fact that, no matter what I do with my life, I’ll always be more mortal than king Etana of Kish. How’s that for a profound influence?