Hammurabi reigned over the Old Babylonian Empire for 42 years from 1792-1750 BC, building the empire from little more than a city state or small kingdom, into an empire that reached from the Persian Gulf in the south, right up the Euphrates to Mari on the edge of modern Syria in the north.

If you’ve heard of Hammurabi (other than on days 4, 8, 18, and 26), it’s probably because of Lex Talionis. And if you haven’t heard of Lex Talionis, no he’s not a Roman general or a Marvel baddy, although he was a particularly nasty character in a short story I once wrote. No, Lex Talionis is the law of retaliation; the “eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth” of Biblical justice. Though in what is starting to get boringly predictable, the authors of the Bible acquired this principle from the Mesopotamians who preceded them, in the Code of Hammurabi.

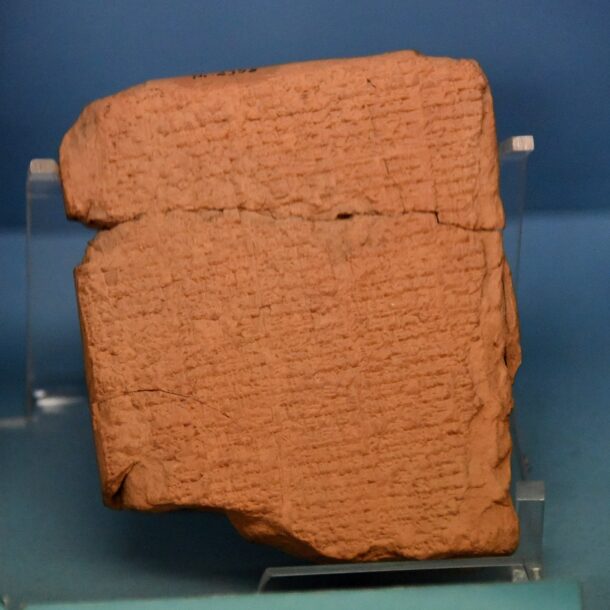

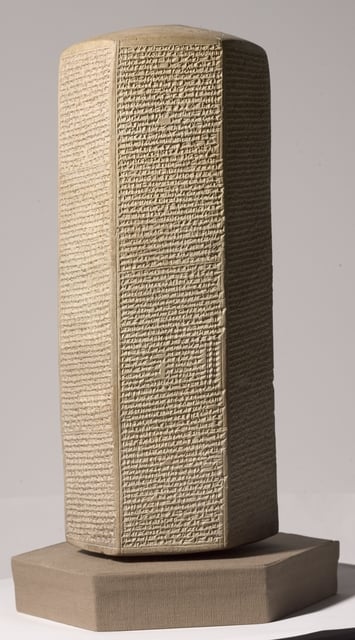

I’ve already shown you the Code of Hammurabi stele in the Louvre, so today’s tablet is a smaller version of the Code in the Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.

But what does “an eye for an eye” mean? It sounds like brutal vengeance. Like the punishment should fit the crime, in the manner of the movie Se7en. It sounds harsh and excessive, but there are two connected reasons to argue that it’s not, or at least wasn’t at the time.

Firstly, it’s better than the typical approach to retaliation – going way over the top in a mafia style: “He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue.” Do you want Albanian blood feuds? Because that’s how you get Albanian blood feuds. Gandhi probably had this interpretation in mind when he said, “an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind”. Human nature is to overestimate the harm done to ourselves by others, and underestimate the harm we inflict as revenge, so without a legal code like that of Hammurabi, cycles of revenge spiral out of control.

Secondly, the interpretation shouldn’t be doggedly literal. It should be read as the injured party should be given “an eye”, not that the transgressor should have an eye taken away. Their attacker’s physical eye is of no value to the now eyepatch-sporting victim. But financial recompense to make up for the pain, suffering, inconvenience, and loss of future earnings? That could actually help.

So, read in the light of these two points, “an eye for an eye” places an upper and a lower bound on financial restitution. The wronged party shouldn’t be making a profit on their compensation, but they should be made whole.

A related question is how this restitution is calculated. A richer person might have to pay more than a poorer one if the financial comparison is made in terms of what they can earn in an hour. This is similar to the system in Finland where eye-watering speeding fines for the mega-rich often make the news overseas. On the face of it, this seems fair. But gradation of punishment by social strata cuts in two ways; what if Mr Moneybags is the victim? We saw on day 18 that punishment varied depending on whether the victim was a gentleman, freeman, or slave. Is it fair that a surgeon’s punishment for injuring a gentleman is greater than that for injuring a slave? Most would say not. This cuts to the heart of what we value. Is it time, as would be implied by all lives being equally valuable? Or is it money, assets, or social status? Are “some… more equal than others”?