Card number three in this week’s royal flush is king Sennacherib, who reigned over the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705 to 681 BC. You may remember him as a fan of skewered locusts (day 30). You may also remember Byron’s poem, The Destruction of Sennacherib, or at least the line “The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold”, used as the textbook example of anapestic tetrameter (along with “Twas the night before Christmas and all though the house…”). But I don’t want to talk about his insectivorous proclivities, or his catastrophic attack on Jerusalem (a rare defeat for this hugely successful leader). Instead, we’re concerned with one of the great wonders of the ancient world: the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

“Hold up,” you may be saying to yourself, “don’t you mean Nebuchadnezzar II?”, and you’d be right that that Nebuchadnezzar is the king most commonly associated with this wonder. But only one source, the Roman historian Josephus, actually names him. No archaeological remains have been found in his capital city of Babylon to corroborate his description. We have no contemporary mention of a garden built at Babylon, which is a significant omission given that comprehensive records of Nebuchadnezzar’s works in Babylon go into such detail as the names of streets. These absences have led some to think that perhaps Josephus writing in the 1st century AD or his source, the priest Berossus writing some three centuries earlier around 290 BC, was mistaken.

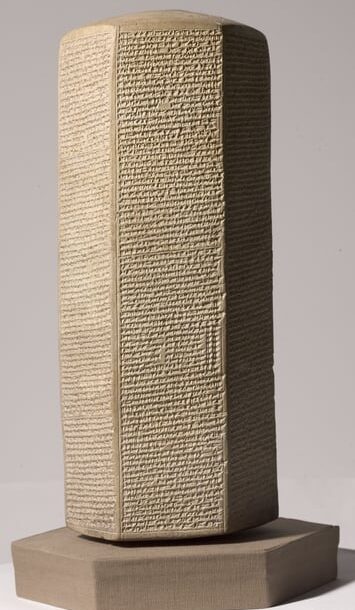

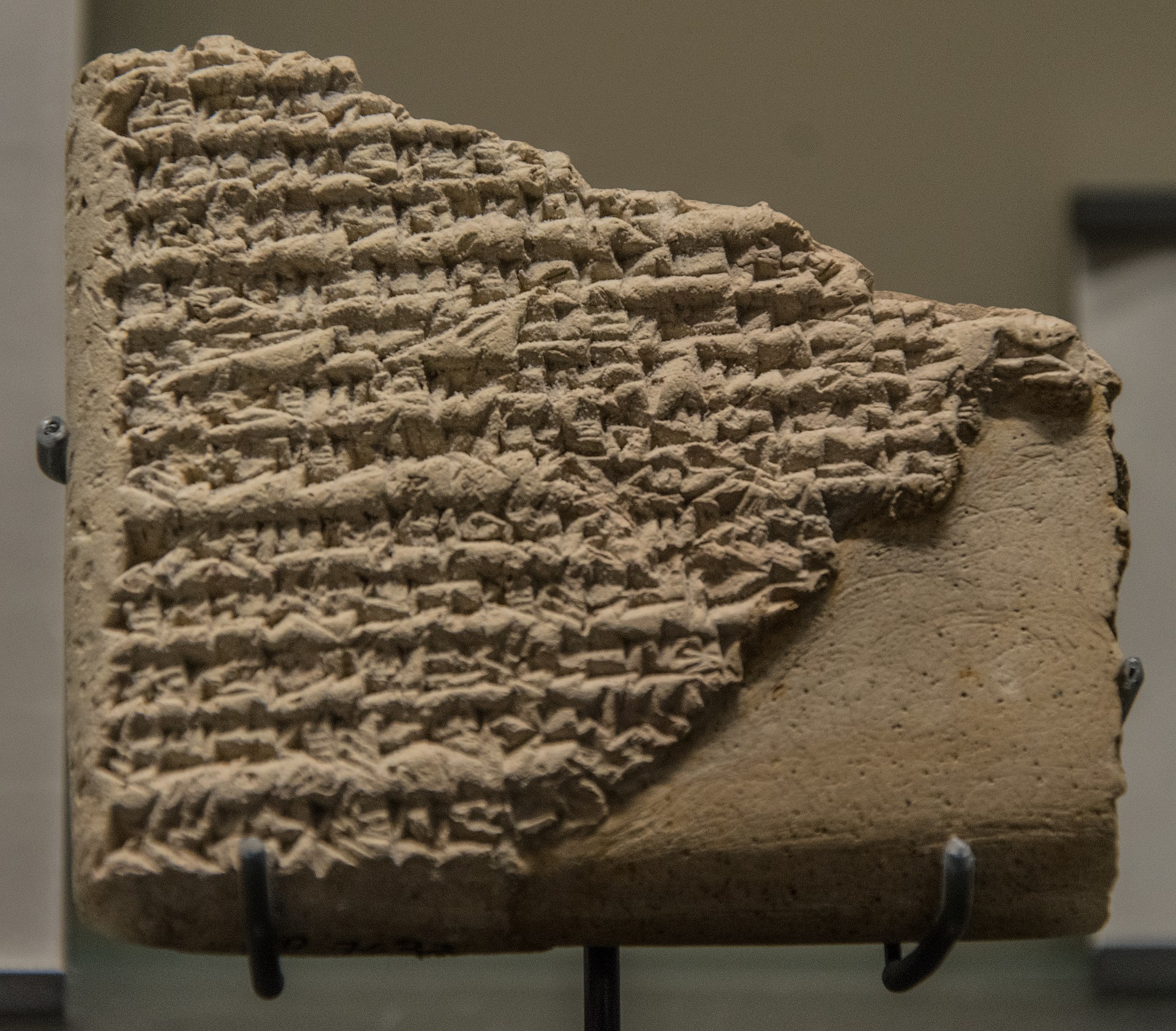

What did exist is Sennacherib’s fabulous garden at Nineveh, his capital city. The descriptions are comparable with those of the gardens of Babylon, and it clearly merits inclusion in the panoply of ancient wonders. These gardens, featuring running streams and planted with forest trees in imitation of a natural mountain landscape, were in their prime by the time of Ashurbanipal (look out for him on day 49), and are shown in panels decorating his palace. We know of these gardens not only from later writers and stone-carvers, but also from Sennacherib’s own inscription, describing the great works of his reign on three prisms, like that in today’s picture which is now at the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

One compelling detail of the Greek geographer and historian Strabo’s description of the Hanging Gardens is the use of a screw device to raise water for the garden. If this is in fact what we know nowadays as an Archimedes’ screw, the invention predates Archimedes himself by at least 350 years. Remains of the civil engineering works bringing water to the city from almost a hundred miles away are still visible to this day.

Whether or not the garden at Nineveh is the true Hanging Gardens of Babylon is a mystery that may never be resolved. That doesn’t change the fact that Sennacherib, as well as being one of the greatest conquering emperors in ancient Mesopotamia, also ranks among the greatest gardeners and engineers of history.