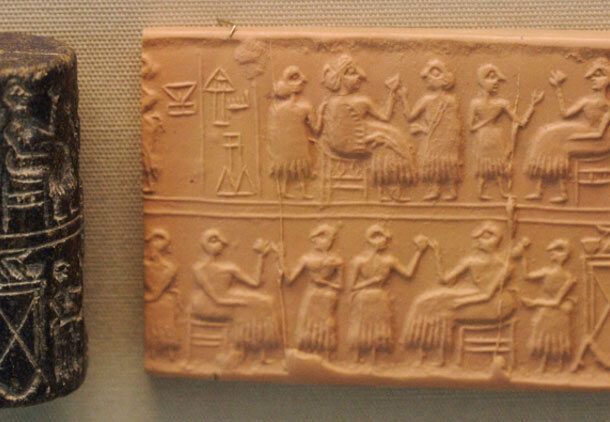

The time, around 2500 BC. The place, the Royal Cemetery of Ur. Queen Puabi is dead and adjacent to her burial chamber are a retinue of attendants, guards, and musicians, decked out in the finest jewellery, armour, and accompanied by the finest of ornamented instruments. All also dead. This find is the jewel in the crown of archaeologist Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur in the 1920s and 1930s. The grave he named PG 800 contained a female, Puabi, with three engraved cylinder seals, one of which you can see here. The accompanying “death pit” contained five armed men, four grooms for a pair of oxen, another three attendants, and twelve female attendants.

Woolley excavated over 2100 graves in the Royal Cemetery and estimated it to have had twice that number. Sixteen of the graves were identified by Woolley as royal tombs, due to finds of cylinder seals with names and royal titles, and accompanying death pits, all from a period of around a century between 2600 and 2450 BC in the Early Dynastic period (day 24). The grave of Queen Puabi is the source of by far the richest assortment of grave goods including a golden headdress, a golden lyre decorated with the figure of a bull, a set of gold tableware, and a silver chariot. The finds are now variously in the British Museum and the Natural History Museum in London, Penn Museum in Philadelphia, and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

The queen’s entourage were hypothesised by Woolley to have walked into the death pit and consumed their poisoned draught willingly, like a far-flung precursor to the 1978 Jonestown Massacre in which 918 members of the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, a socialist religious cult, poisoned themselves. Their leader, Jim Jones, believed (probably erroneously) that an attack by the CIA was imminent and ordered “revolutionary suicide” by drinking a poisoned drink. This is where we get the phrase “drinking the Kool Aid” meaning blindly accepting what we are told.

Not drinking Woolley’s Kool-Aid, in 2012 Baadsgaard, Monge and Zettler re-examined the evidence for suicide. The artifacts recovered by Woolley included six skulls, which were recovered as they were found, stabilised with paraffin wax and fabric for transportation. This careful recovery meant that they could be scanned using modern techniques. CT scans of two of the skulls now at Penn Museum, found both to have skull fractures, inflicted at or before the time of death, probably with a pointed axe or a small hammer. This changes the narrative from a peaceful, voluntary self-sacrifice to a bloody ritual of mass murder.

Seriously, if you have a sensitive disposition, or are currently eating, I suggest you skip the rest of this paragraph. Oestigaard, in his review of human sacrifice, discusses three modes of corpse preparation, raw, cooked, or burned. The corpses in the royal death pits show signs of the second of these. The bones appear to have been heated, but not directly exposed to fire; perhaps the bodies were smoked to preserve them before they were arranged, delaying the advance of putrefaction in order that they could be viewed for longer in their macabre tableau vivant.

A complete lack of textual records means that we have no insight into the reasons for this planned and elaborate event. Was is sacred or profane? Ritual or political? Were they gifts to the gods? Attendants for the next life? Was it straight-up conspicuous consumption? And what does it mean that this practice died out after only a 100 or so years? Perhaps one day more will emerge, but for now, all we have is the evidence from Woolley’s dig and speculation.