If you’ve spent lockdown learning a language, then according to Judeo-Christian legend, you should thank god for giving you the opportunity.

Cuarón’s dystopian masterpiece Children of Men is drawn from the 1992 novel by P.D. James’, whose title according to Cuarón was inspired by the phrase, “Thou turnest man to destruction; and sayest, Return, ye children of men” from Psalm 90. The phrase also appears in 10 other psalms, but its first appearance in the bible comes in Genesis 11:

“And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded.

And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.”

The story is that of the Tower of Babel and contains another example of an ancient pun. In a piece of wordplay typical of the original Jahwist authors, the name of the city of Babel is related to the Hebrew word “bālal” meaning to jumble or confuse. It also works in English where we have Babel/babble – a rare gift to translators, who usually must work much harder to maintain wordplay in their translation.

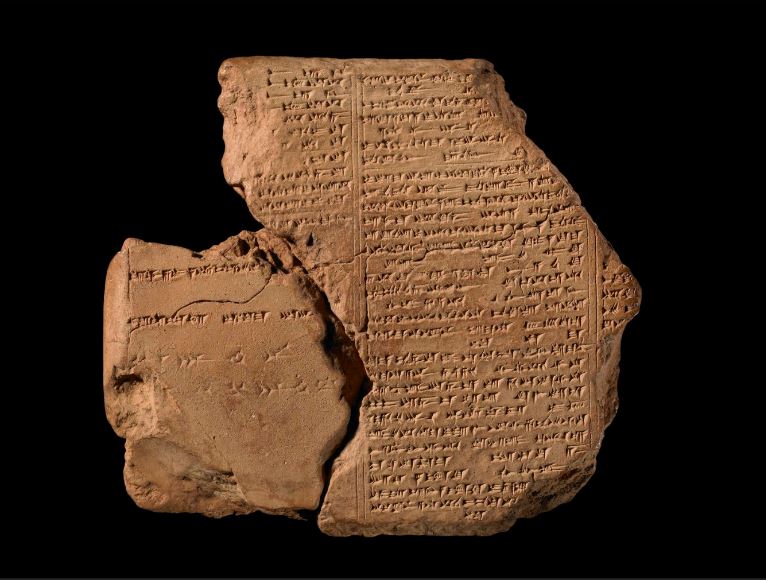

There’s something about this tower that inspires the urge to destroy. Today’s cuneiform source comes again from the Schøyen Collection (like the bulla on day 22), where it had sat ignored for many years. In 2017, it was finally recognised as relating to a great ziggurat in Babylon built by Nebuchadnezzar II. Figuring out the contents of this stele was hampered by the fact that the middle of the inscription has been destroyed, possibly by Xerxes of the Achaemenids, son and successor to Darius the Great (day 28), when he conquered Babylon. Usually this was done as a precursor to replacing the inscription with one glorifying the conquerors, but for some reason this one was left incomplete.

There’s more than a little to pique the interest of Freud in the story of the Tower of Babel. Nebuchadnezzar II’s massive erection, reaching up into the sky, wagging in the face of God, and causing him to get angry and take out that anger on the tower like some ancient Bin Laden. Penis envy much? Well, if God made Adam in his image, and the tiddly appendage on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is anything to go by, maybe that’s not such a surprise.

In any case, those of us who love languages must thank God, no matter His jealous motivations. Of course, as an origin myth, the story is transparently wrong, since language set off on its path of evolution much earlier than the 6th century BC.

I use the word evolution advisedly. Sir William Jones, not Charles Darwin, was the first person to describe evolution. Jones was a supremely gifted linguist, said to have mastered 28 languages, including ancient Greek, Latin, Persian, and Arabic, right up to modern European languages. And crucially, Sanskrit. As part of his attempts to translate Sanskrit texts, and put order on the connections he saw between this ancient language and other later languages he basically invented the field of comparative linguistics. The link to evolution was in his use of the technique of dendrograms – think of the tree of life you saw in biology textbooks – to visualise the connections between languages, relating them back to a hypothetical common root, Proto-Indo-European or PIE. These were already used in biology for mapping the relationships between species, but until Darwin came along, they were assumed to be static descriptions. In using them to classify languages, Jones was implicitly adding a time dimension to the analysis, with forking branches representing languages diverging and cross-pollinating at different times in history.

So, the plethora of languages we both struggle with and delight in were brought to us not an angry and jealous god, but through a process of memetic evolution modulated by the pressure of social selection.

I’ll leave the last thought to Emily Tamkin writing in the New Statesman about learning Yiddish during the lockdown: “You are telling yourself that you’ll have time to keep learning this language. That you’ll be able to get better at it. You start something so as to be able to see it through.” Words to live by.