Just what is the difference between prose and poetry? In keeping with our theme this week, the key distinction is that poetry is designed to be heard. It’s hard to recall the “slap and pop” of the frogs, “cocked / on sods… their blunt heads farting” in Seamus Heaney’s Death of a Naturalist, combining onomatopoeia and assonance, without hearing his Irish-accented voice reading it aloud beside a pond.

Alas, too little is known about Sumerian poetry to even begin to put together the rhythm and flow of a Sumerian poem. By contrast, more is known about the sounds of Akkadian poetry, although there is still much debate, wildly divergent opinion, and scholarly dissing to be found in the academic literature: “It is painful to see a man tying himself in such knots in public” writes M.L. West about the Dutch scholar F.M.Th. de Liagre Böhl’s theorising.

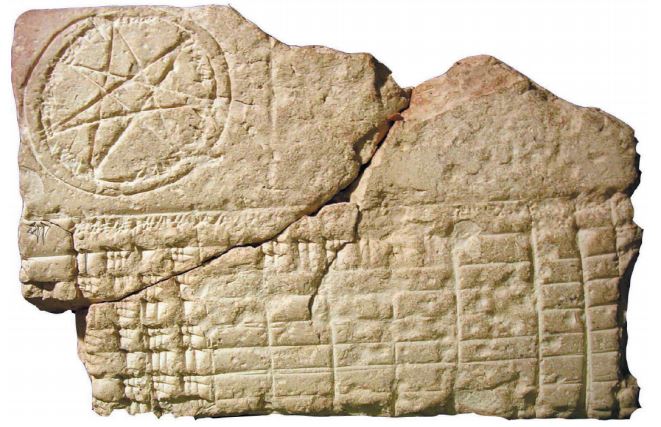

Much Akkadian poetry follows more or less regular rules. The main structural unit was the line. Lines were further split into two or more sections, with each section forming some kind of natural unit of meaning. Lines were grouped into stanzas, frequently quatrains. Although rules are made to be broken. Saggil-kinam-ubbib identifies himself by means of an acrostic in his 297 line poem known as The Babylonian Theodicy, in which each stanza of eleven lines begins with characters that sound out “I, Saggil-kinam-ubbib, the incantation priest, am an adorant of the god and the king”. It’s clear that he had at least one eye on the reader rather than the listener, since it’s unlikely that even a very careful ear would pick on up on this conceit. Our tablet of the day is part of a commentary on this long and complex composition, written to help explain some of the difficult vocabulary to later scribes and students.

If the vocabulary of the piece was difficult for students tens or hundreds of years after the lines were written, they would have at least had the benefit of hearing the piece performed live. Nowadays, scholars can only speculate and test their nascent intuitions against the source material. It was for one of these intuitions that West criticised de Liagre Böhl, or rather for the fact that his theory of an “alternating metric” had no basis in evidence and was merely his “intuitive preconception”.

Erratic metre, according to West’s own suggestion, may have been covered up by something that sounded much like religious chanting – similar to the “prophecy tone” style of reciting readings from the Old Testament, in which the middle of a line may squeeze in extra accented syllables, and the middle and end of the lines are often marked by a falling intonation. This fits with the fact that lines in Akkadian often end with a longer sound. Think of a priest half-singing, half-reciting mass, stretching out the final syllable of a verse, and you have an idea of the sort of thing he means. It is tempting, even haunting, to think of this tradition of chanting poetry as something unbroken since Babylon.

Day 39 – poetry