Quite apart from thanking him for opening up the world of cuneiform to me, I definitely have Fred to thank for today’s topic. Way back on his day 22 (my day 18), he posted a tablet containing an Ugaritic song known as the Hurrian Hymn. At 3500 years old it’s the oldest song to which we know the melody, and it’s a window into the fascinating field where ancient musicology overlaps with Akkadian philology.

The Hurrian people lived on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, quite some distance from Mesopotamia, and spoke a different language. However, with Akkadian being a lingua franca, their scholars would have been familiar with it, if not totally proficient. Anne Draffkorn Kilmer describes one tablet as being written “in a garbled, barbaric Akkadian, presumably the work of a Hurrian scribe”. Many of the same technical terms are found on tablets in both languages.

Writing in 1969, Kilmer tells the story of early attempts to find a music theory in sumero-akkadian cuneiform tablets. One find in KAR 4, called “Aameme” after its first syllables, was thought to contain music theory. That turned out to have been a little optimistic – yet another example of people seeing patterns where there was no real pattern to be seen: apophrenia, as William Gibson calls it. The tablet was eventually reinterpreted as a lexical list of personal names. This kind of error must have happened so many times in the early days of the modern study of cuneiform. We’re hard-wired to see patterns everywhere. It’s the driving force behind superstition, but also science. The dividing line being whether hypotheses are tested, and most importantly, discarded if evidence appears which shows the pattern to be mere chance. An ephemeral face glimpsed in a cloud.

What is amazing about the scholarship in those far-off days of the late 1960s is that rather than Google and the specialised databases of CDLI and the like, the tools available were library cards and the fallible memories of researchers. Kilmer describes the chain of realisations and mental leaps that allowed her to link certain mathematical texts with other musical texts, in order to attempt to reconstruct the scales of Babylonian music.

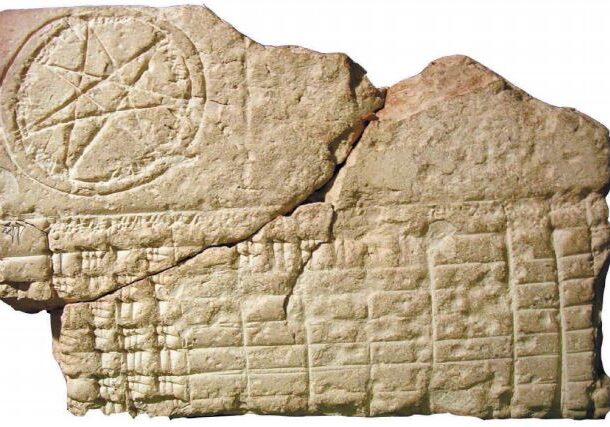

Today’s tablet is one such text. It’s unusual in that it contains an illustration – a seven-pointed star inside two circles. Below that is a table, which looks for all the world like it comes from an Excel spreadsheet, and is proposed to be a tuning chart for a seven-stringed instrument.

Songs came in several different flavours, and it seems as thought the instruments were tuned to different scales. Amazingly, one of the scales recovered is precisely our major scale – of “do-re-mi” fame. In the lists of songs that have been uncovered, the category name for love songs was “breast” songs, which Kilmer suggests may be because the instrument used was played held against the musician’s chest. I prefer to think that we might call them songs of the heart. So sing out loud, from the heart, in the name of Ea/Enki!