This week I’m mostly having my life profoundly changed by tablets related to the sounds of Mesopotamia. How can that be, given that characters impressed in clay or carved in stone are silent? That’s a good question.

Sumerian is principally a logogrammatic script. In the very early stages of protocuneiform, concepts are represented by recognisable images. Over time, these become less and less recognisable, and they also become combined, for example when the logogram from “head” is combined with that for “food”, it means “eating”. This nature means it’s particularly difficult to know how the language sounded. Most signs contain no phonetic information. An exception is found in signs which convey aspects of grammar. CJ Gadd put it neatly when he wrote: “Sumerian writing is a combination of pictorial and phonetic writing [in which] for the most part, the former constitutes the skeleton of the speech, and the latter covers it in the flesh of grammatical coherence.” In the example he takes, the sign for mouth, “ka” is used in the phrase “lugal abzu-ka”, meaning “king of the deep”, where “lugal” means “king”, and “abzu” means “the deep”. Unless we are to read this as something like “king of the deep throat” (and I stress that this is my suggestion, not that of the venerable CJ Gadd), “ka” must be serving some other purpose.

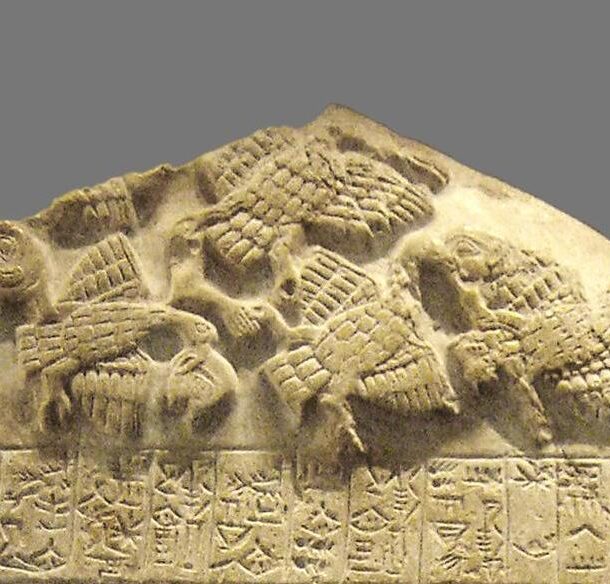

This talk of flesh and bones is appropriate to Gadd’s example, since its likely source is the Vulture Stele, which we saw on day 24. Today’s image is a part of this stele showing the vultures carrying off the severed head of a fighter.

Grammatical affixes, like “ka”, function as a rebus – a kind of word game. For example, the rebus “👁 ♡ BB” encodes the three words “I love bees”. In this phrase, the eye sign is phonetic, representing the homophone “I”. The heart sign is a logogram, representing the concept of “love”. The B sign is again phonetic, because it sounds like “bee”, and when repeated makes Bs – “bees”. Likewise, in some contexts the word “ka” literally means “mouth”, but in others it’s used because it sounds like the word-ending that encodes part of the grammar of Sumerian.

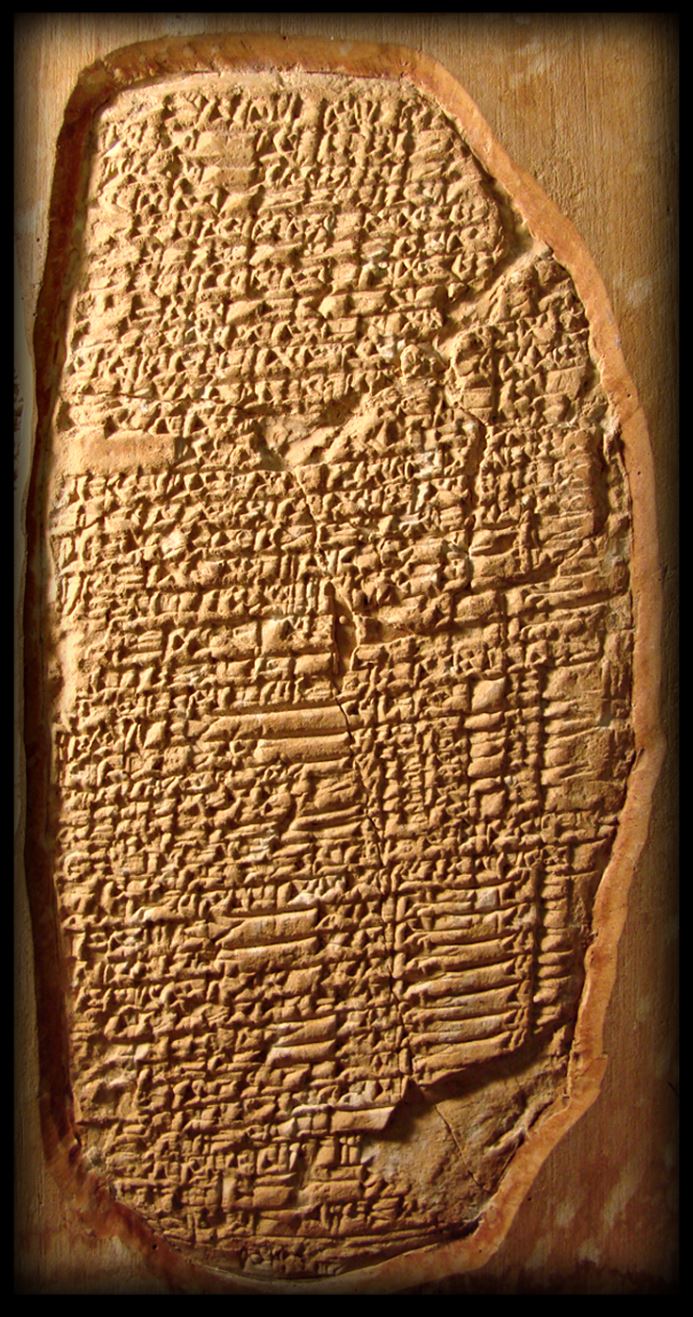

If we only have this very small amount of grammatical flesh on logogrammatic bones, how do we know what Sumerian sounded like? The honest answer is that we don’t. Sumerian is a completely extinct language. It is also an isolate, not related to any living language, despite what some generally nationalistic scholars will tell you about Turkish, Hungarian, Finnish (to name only the least unlikely candidates). But we’re not completely in the dark; Sumerian survived for a long time alongside Akkadian and other ancient languages like Aramaic. As we’ve seen before (day 25), there are many bilingual tablets, and fortuitously for us, Akkadian cuneiform was a predominantly phonetic script.

So now we’ve pushed the question back to “how do we know what Akkadian sounded like?” That we’ll get on to tomorrow.