Continuing our theme of fermentation, vinegar is the product of a secondary fermentation of sugars. The first stage takes us from sugar to alcohol, through the action of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer’s yeast), and the second from alcohol to acetic acid by one of the members of the Acetobacter genus. Like accidentally risen bread, accidentally producing malt vinegar from spoiled beer was likely harder to avoid than to make happen.

That the Mesopotamians used vinegar in their kitchens is evidenced by the Yale Culinary Tablets, which we’ve touched on before. One recipe for roast wild hens (francolins) has the chef first sear the birds, rinse with cold water, sprinkle with vinegar and rub with crushed mint and salt, before stewing them in a broth of beer and water with leeks, garlic, and other aromatics. The meat would be served accompanied by fresh greens, garlic, more vinegar and salt.

Searching for translated mentions of vinegar in the CDLI online database of cuneiform tablets, I found only one: a line reading “Vinegar Field”. I popped it into Google and came up with an interesting book. Days at the Factories, written by George Dodd in 1843, in which he describes the vinegar-field of a vinegar-works, arrayed with row upon row of casks all elevated on bricks like wheel-less cars in a particularly crime-struck carpark. But on a more careful reading, it became clear that this isn’t what the Sumerian term denotes. It actually forms part of a list of field names: “The field Little Marsh, the field Kimura, the field Little Canebrake, Vinegar Field, … (this) is the list (of fields) of the artisan”. Also, there was no picture of the tablets from which this text was compiled, so I needed to keep digging.

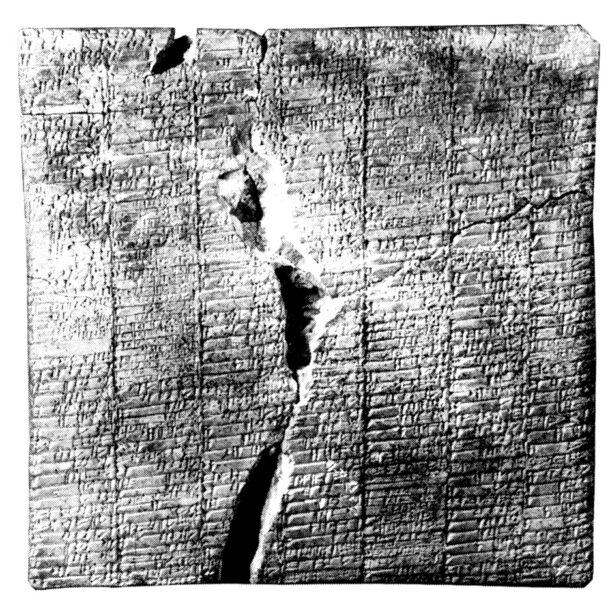

What it did provide was a transliteration of the word for vinegar in Sumerian of the Uruk III period – “a-gesztin-na”. The word appears 108 times in the Uruk III corpus, though I should mention that it seems like 62 of those mentions are from the tablet I’m posting today. Strangely, several of those are again found in conjunction with “a-sza3” for field, and with quantities measured in “gur” and “barig”. The tablet is untranslated, but my best wild-ass guess is that it records quantities of something produced in a field called Vinegar Field. A gur was a large measure of volume, and a barig was a smaller but still large quantity, so the product of a field could be of the right order of magnitude.

Searching like this for a transliteration rather than a translation showed me just how much cuneiform remains below the translated surface. A huge quantity of cuneiform tablets have not even gone through the first stage of “fermentation” – they’re still raw sugars. Others have been through the first fermentation into phonetic/logogrammatic (or alcoholic in our extended metaphor) transliterations. Only a small proportion have reached the vinegar stage, being translated to a modern language for those of us who don’t (yet!) have a working grasp of transliterated Sumero-Akkadian.

To use another metaphor, it’s as though we’re in the middle of an archaeological dig and are mainly just cataloguing potsherds from the surface, only sinking a deeper trench when the sherds appear to be from a literary text, or something extraordinary like the Yale Culinary Tablets, with the overwhelming majority of the site remaining unexplored.