There are various ways of making meats fit for consumption, including smoking, roasting, freezing, drying, and fermenting. Some types of dry-cured sausage come under the both the drying and fermenting categories. An example would be sujuk (sucuk in Turkey), of which I’ve tried the horse variety in Bulgaria, and which is also commonly found in modern Iraqi cuisine. I’ve not been able to find any direct evidence, many books on the history of meat processing in general, and sausages in particular, posit the origins of sausages in Sumer.

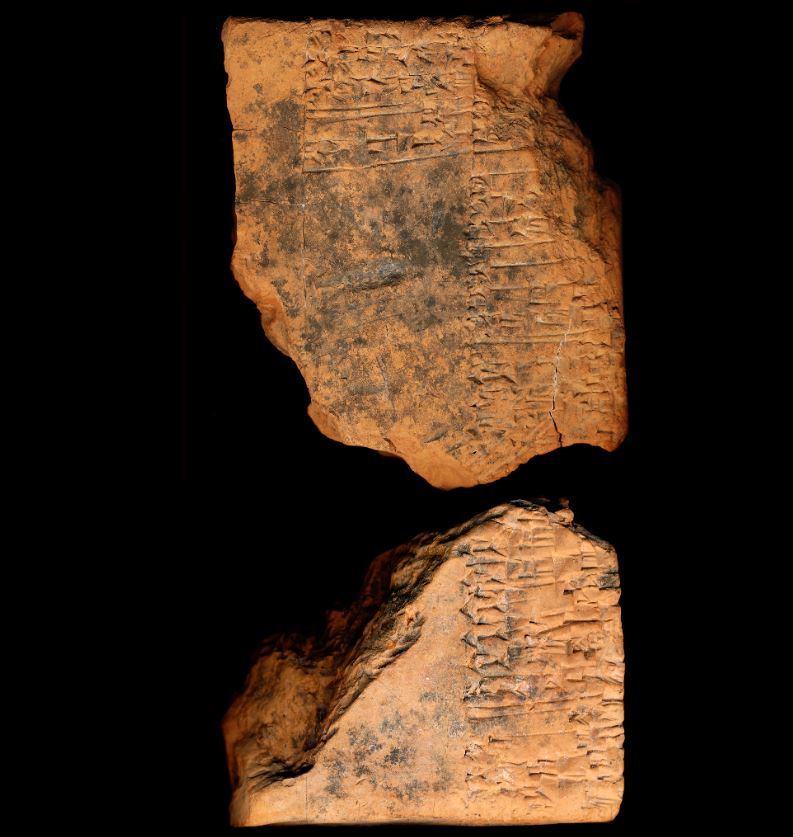

While the existence of Sumerian sausage must remain a supposition, today’s tablet tells a related tale. It’s another food list, this time in Sumerian and from around 1900–1600 BC, containing a list of different breads, followed by many different dried and salted meats, including cuts of beef, lamb and mutton, goat, pork and venison.

Meat was a valuable product, not eaten every day outside of the palaces. It would have been imperative to find ways to store it and to avoid waste. The Sumerians were an innovative bunch, so many assume that those handy sausage casings that come inside animals would have been forced into service to hold together the leftover scraps of meat while they were salted and dried. As with their other recipes, it’s likely that Sumerian sausages would have been heavily flavoured and spiced.

Dry curing whole cuts of meat is a simpler and safer process than making sausages since the inside of the muscle remains sealed and so protected from bacterial action. Sausages involve ground or chopped meat, and so bacteria can penetrate all the way through the mixture. For this reason, modern sausage use curing salts which contain nitrates. There is little in the way of nitrates in sea water, or the other sources of salt in Mesopotamia like the salt domes of Basra, but nitrates can be won by juicing vegetables and drying the juice. Beets and spinach both have relatively high concentrations and so perhaps these would have been used in the process.

Salt was not just for food in ancient times. Salting the earth, was famously (although unverifiably) done by the Romans after their defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It was also said to have happened at Hunusa after it was conquered by the Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser I. It appears this was more symbolic than an act to truly lay waste to the soil, but we do know that salt can have that effect. Increasing salt concentrations in the Tigris and Euphrates deltas played a part in declining crop yields there, and so reducing the economic and political power of Sumer. I found a modern reference to a project to “prevent the Mesopotamia-ization of vast swaths of the Central Valley [in California]”, showing the continued association of salt accumulation in that part of the world with similar problems today.

So salt can destroy, or it can preserve. Similarly the action of bacteria on foods. When it goes right, they can produce some wonderful goodies for the store cupboard. When it goes wrong, slimy textures and nasty stomach cramps at best, and death by botulism at worst.