Fermentation is one of the most magical things that humanity ever discovered. How poor would culinary life be without bread, beer, wine, yoghurt, cured meats, vinegar, sour pickles, kimchi, soy sauce, Lee & Perrins, thousands upon thousands of varieties of cheese, and untold other delicious riches? This week we’ll be digging through cuneiform tablets that deal with fermented foods and drinks, and exploring the many ways they both reflected and influenced society in ancient Mesopotamia.

During the recent months of lockdown, we concluded that the best way to have fresh bread while limiting our trips to the supermarket, was to bake our own. Everyone else seemed to have come to the same conclusion, and so around here yeast was rarer than rhenium. There wasn’t a block of fresh yeast to be had at any of the supermarkets in any of the streets around our flat here in Barcelona. What to do? Well if Instagram is anything to go by, the answer was startlingly obvious. Everyone took the same next step and set themself to procuring or producing some sourdough starter. In this, they were following in a baking tradition that is at least 9000 years old, and likely even older.

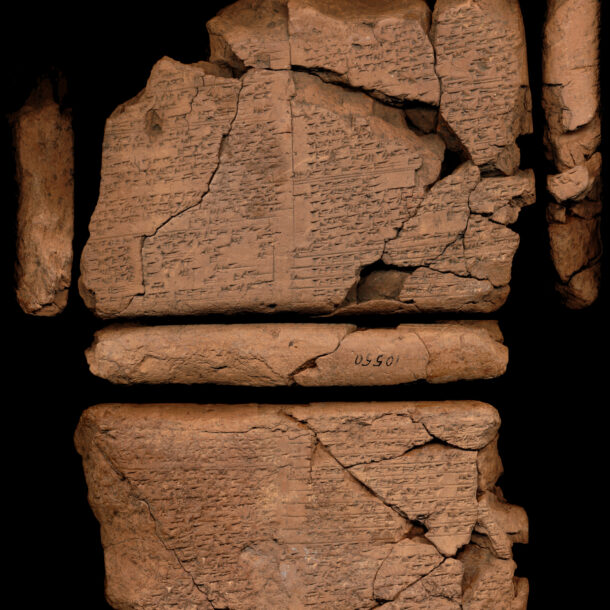

Today’s tablet, probably written sometime after 1233 BC, records temple offerings to the gods of Assur, capital of the Assyrian Empire (the Assyrians loved their bread – another Assyrian collection contains two tablets listing 200 to 300 distinct types). Among other offerings, the image today lists a handful of breads and details the types and quantities of flour provided to produce them. Ginû bread, qadūtu bread, and the midru-bread used in offerings to the god Aššur, as well as sweetened cakes, and more beer than a Tolkein tavern to wash it down.

Emmer, einkorn and barley were the three most common grains at the end of the Ubaid period and the start of the Sumerian period proper. These were all domesticated grains and were all processed into flour for breadmaking. There was none of the standardised, commercially-homogenous yeast that we can once again get our hands on, but as we have all learned, that’s no insurmountable obstacle: the air is billowing with wild yeasts (though not as much as some sourdough enthusiasts would have you believe); fresh fruits are dusted with a fine, powdery bloom; the flour itself contains a whole host of yeast spores. For these early bakers, it may have been harder to stop their grain porridge from fermenting than it was to get it started.

That’s not to say that their bread was necessarily leavened. They would have consumed their fair share of flatbreads, especially since they used more barley, which doesn’t have the gluten content of wheat that helps it to hold a wild open crumb. There are clear references to “risen bread” and of dough rising in the Yale culinary tablets of which we’ll see more later this week. This process must have been like magic, this transubstantiation of flat porridge or dough into a light, airy bread. Of course the products of fermentation were popular with the gods! Is it any wonder that the transubstantiation held sacred by the Catholic church involves wine and bread becoming the literal blood and body of Christ?