The Babylonian Empire was much more enduring than the preceding Akkadian Empire. It arose in 1894 BC, but truly came into being 100 years later in 1792 BC when Hammurabi came to power.

These dates may seem precise, but in fact they should be read with caution. Obviously, the Babylonians didn’t use the same calendar as we do. The way they referred to years was something like “in the 4th year of the reign of Itti-Marduk-balāṭu”. I’ve seen a few references to the “long chronology”, the “short chronology”, but while reading the Wikipedia article on Babylonia, I came across a section that opened my eyes to quite how foggy these dates are.

The section that pulled me up short was about the sack of Babylon by Mursili I, king of the Hittites. While the sacking was a roaring success for Mursili I, his return home was a swift reversal of fortune: he was assassinated shortly after arriving back to Hattusa. The sacking is a key date for tying together various threads of what are called “floating chronologies”. Floating chronologies are timelines where we know how many years passed between specific events, but we have nothing to pin it down relative to today.

The only time I’ve come across this term before is in relation to dendrochronology. Dendrochronology is the science of dating wooden objects by looking at the growth rings that run through them. A good year’s weather produces a wider ring than a poor year’s, rather like a prosperous year adds more inches to my belt than a meagre one. By placing two trees from the same area alongside each other, it’s possible to match up the fat and the lean in a process called cross-dating. By linking up trees that sprouted, flourished and died in different but overlapping time periods, we can read a record of climate change going back for tens of hundreds of years. Much of the difficulty comes from the fact that trees even a short distance apart can experience different weather patterns, and also that ancient timber may be found far from where it grew.

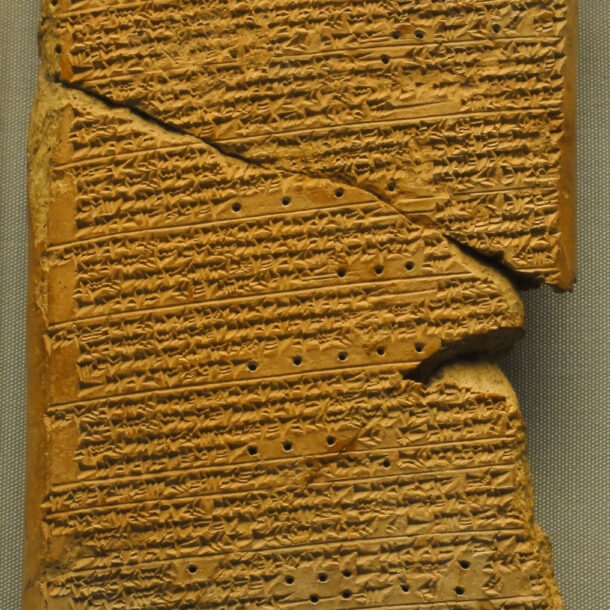

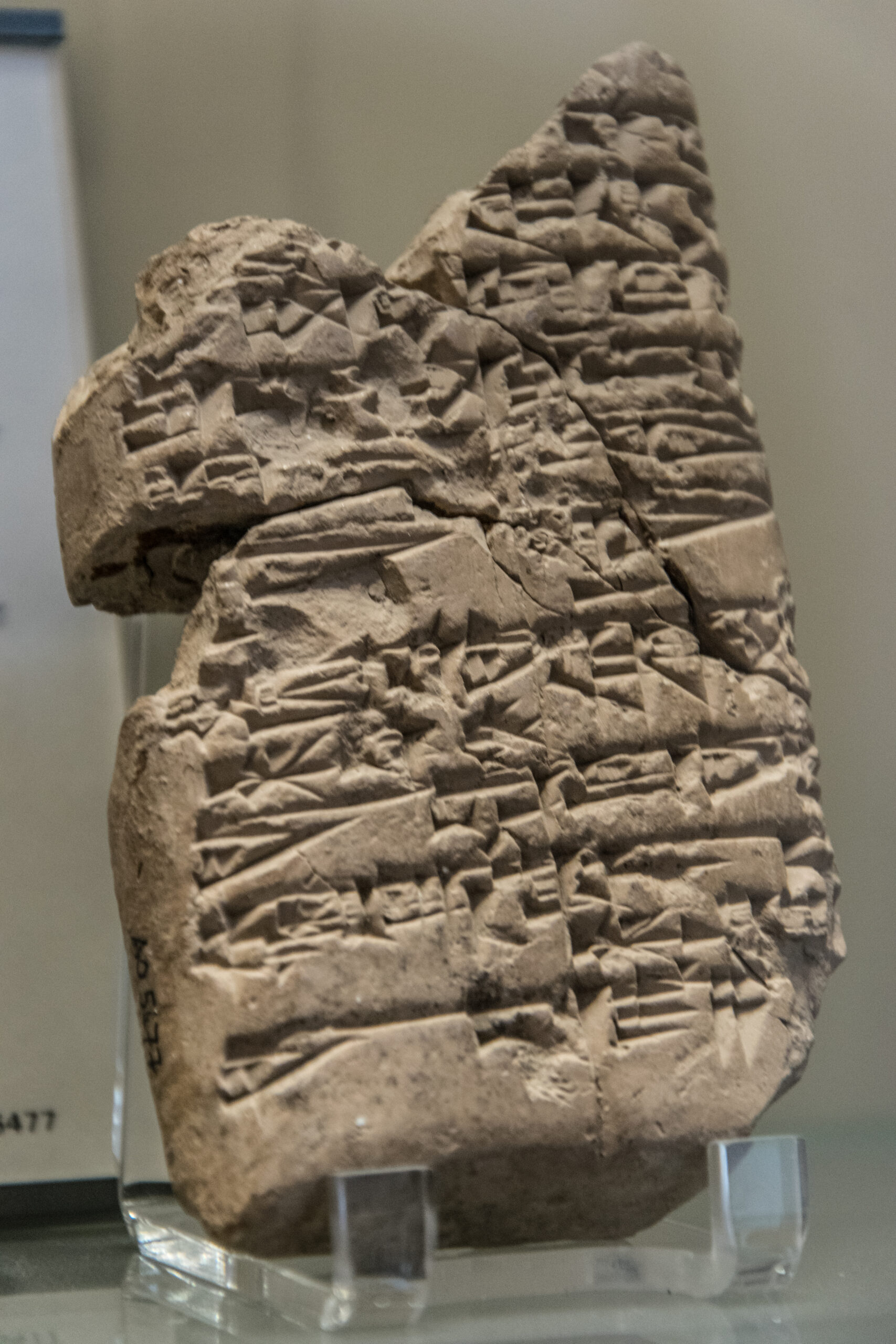

So far, dendrochronology has not been helpful in reconciling ancient near eastern chronologies, but it makes for nice metaphor. One of the primary types of artifacts that inform us about chronologies is the kings list. These lists give us reigns of differing lengths, like rings of differing widths. They overlap and can give us a chain of reigns but without fixed point of reference. And like the rings of those near-neighbour trees with different weather patterns, different kings lists may magnify or minimise the reigns of certain rulers, though for political reasons rather than climatic ones. Another type of evidence is in records of celestial movements, like the Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa you’re seeing today.

But back to the sacking. The event in question happened in 1531 BC in the short chronology, and in 1651 BC in the long chronology. But there’s not just the long and the short of it. There’s also the middle of it (1595 BC). And the ultra-short and ultra-long of it (1499 BC and 1736 BC). I worry what room for manoeuvre remains in case some new point of debate arises. The shorter-than-short-but-longer-than-ultra-short chronology doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue.

And those foggy dates in the first paragraph? They’re in the middle chronology, in which the Empire would endure until 539 BC, save for a few centuries of occupation by the Assyrians (tomorrow). That’s twelve and a half centuries of near-continuous dominance in southern Mesopotamia, until Babylonia and Assyria both were sucked up into the Achaemenid Empire (the day after).