The Uruk period stretches from the late Chalcolithic period, characterised by copper and stone tools, to the Early Bronze Age, which begins when metalworkers learned that adding tin to copper yielded a better metal for tools and weapons. As the period opens, a few temple cities existed, some already with populations of over 10,000 people, but by and large the population and culture remained rooted in the agricultural way of life. Nisaba, whom we saw on day 1 symbolised by grain, was the preeminent goddess of vegetation and was in her heyday during this period. As the period went on and became more urban-focused, however, she would become less and less associated with grain and agriculture and more with scribes and writing.

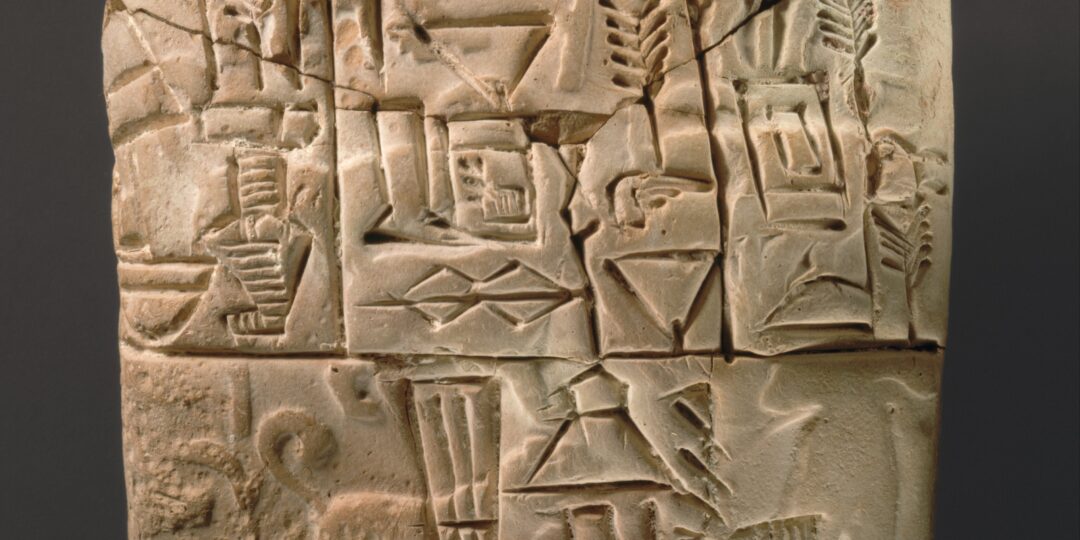

This protocuneiform tablet I’m being profoundly influenced by today, probably from Uruk and now in Met Museum in New York, is an early example recording grain distribution in the characteristic drawn pictograms, rather than the later true cuneiform writing.

By the end of the period, the city of Uruk (from which modern-day Iraq gets its name) had more than 50,000 inhabitants, making it the largest urban centre in the world. Agriculture, and then urbanisation, were both forces that led to much greater differentiation of roles in society, and to stratification of society into unequal layers. Though life must have been unequal before this time, the gap between rich and poor really began to grow once communities began to settle in one place and were able to accumulate wealth. This disparity must have been frustrating for individuals toiling in the mud, digging irrigation channels and the like. Frustration leads to discontentment, discontentment to rebellion, and rebellion to the collapse of entire civilisations.

So how did society in the Ubaid and Uruk periods remain as stable as it did?

Here we see another one of those big ideas, propagating like genes, evolving a society better fitted to growing in its environment. Denis J Murphy describes the development of religion in this period as an adaptive response at the community level: a prosocial change in the way people viewed the natural order of things. The forms of religion that developed in this period gave them a packaged explanation for inequality. In gripping tales and songs of how the world came to be, the creation of mankind was explained as an explicit act on the part of the gods to make life easier for themselves. In return, the gods took care of their people, protecting them from demons and unfriendly gods.

The local big man looks after his settlement, the king looks after the local big men, the king’s personal god looks out for the king. And in return, everybody works and pays taxes and tithes. Settlements which didn’t take to this new order would at best remain as small farming communities, at worst be converted forcibly to the new way of doing things.

This imposition on the individual – this worsening of the lot of some members of society for the benefit of society as a whole – marks the beginning of the social contract. The beginning of the state. The Ubaid and Uruk farmers were persuaded, with the help of some great stories, to accept the new social contract and to support and enhance the influence of the growing sphere of people they identified as kin.