This week is going to take us through the shifting civilisations in Mesopotamia, from the very birth of writing up to kings, battles and standing armies. From around 4500 BC to 2500 BC – two millennia – from a small group of Ubaid people processing their harvest, up to the Old Persians inscribing a grand proclamation into a mountain side. There’s no chance whatsoever that I’ll be giving a comprehensive overview of this wide swathe of history, but there’s a lot of colour in the details.

I mentioned way back on day 1 that I thought the domestication of grain might have something to do with our story of the development of cuneiform. Well here we are, back to the first syllable of recorded time, to misquote Hamlet, sat on the flat roof of a clay building with a group of farmers preparing their harvest of wheat for storage.

I’m reading a paper, “A day in the life of an Ubaid household : Archaeobotanical investigations at Kenan Tepe, south-eastern Turkey”, which goes into great detail of the types of grain and other vegetation found in grain processing and storage house in south-eastern Turkey. Like fires in homes, temples, and libraries have preserved the cuneiform tablets we are becoming so fond of, another fire has given us a flash-bulb glimpse into the lives of these farmers.

We know exactly what they were doing when the fire broke out; they were winnowing the harvest on the roof, where the breeze would take away the chaff. But it would also fan the flames that caused the roof to collapse and destroy the house. From the imprints of grains in the baked soil, the researchers reveal the techniques that were being used to separate the chaff. They can tell us how far through the process of threshing, winnowing, and sieving these ancient farmers were by the small amounts of weeds and other plant matter left in amongst the grains.

That’s some staggering detective work by the archaeologists. To take the negative captured in that unexpected blaze and develop it into this picture.

These farmers belonged to the Ubaid civilisation, the first settled civilisation along the Euphrates. Their civilisation was characterised by some pretty amazing pottery, with geometric designs in a slightly greenish clay with chocolate brown patterns, produced on a “slow wheel”. At the end of the Ubaid period, moving into the Uruk period, this domestically-produced pottery style becomes displaced by pots produced by specialist potters in their newly-emerging urban workshops. In the process, sacrificing aesthetics for utilitarianism.

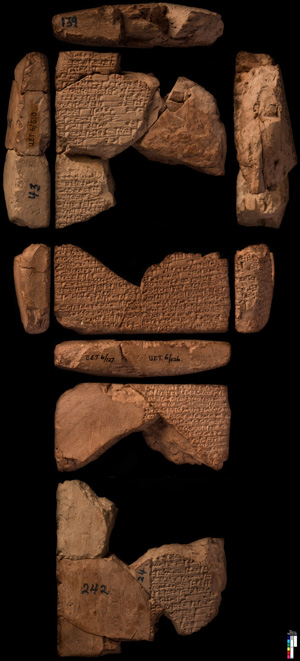

The Ubaid also created a precursor to the precursor to cuneiform. The tokens they used to represent goods came in three-dimensional forms and could be simple shapes, or complex shapes incised with markings. These tokens were enclosed in clay spheres, bullae, like the one you see today from the Schøyen Collection. Bullae could be marked on the outside with symbols representing their contents. These markings would later develop into the stylised pictograms, and would eventually become cuneiform during the time of the Sumerians.

We’ll get on to them tomorrow.