Like today, it could be financially rewarding to be a physician in Babylon in 1700 BC, so long as you were lucky enough to avoid a malpractice suit.

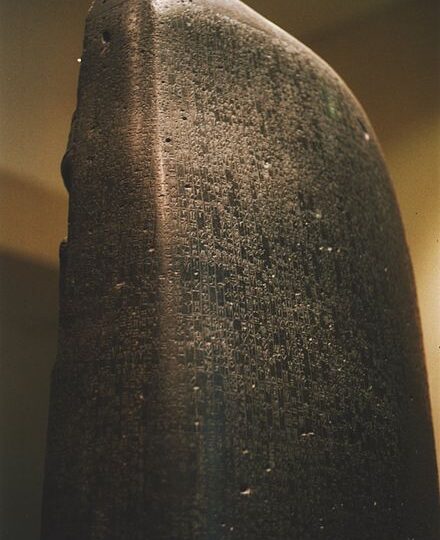

King Hammurabi, he of the embossed brick on day 4, is best known for the collection of laws and judgments recorded in his name on a four-ton diorite stele, which currently stands almost 2 ½ metres tall in the Louvre in Paris. This stone block, inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform, is among the best-known, and best-preserved examples of the script. Today, we’ll see how it regulated reward and punishment for physicians of the day.

Babylonian society under Hammurabi was divided into three classes: awelum, the upper class; mushkenum, the middle class; and wardum, the unfortunate slaves. As “temple priests”, physicians would have belonged to the awelum, though their social status was not as high as the even more priestly exorcists with their esoteric knowledge. Medical fees were set on a sliding scale, based on these social strata. Those who were assumed to be able to afford to pay the higher rates subsidised those with less ability to pay, much like means-tested healthcare services in modern societies.

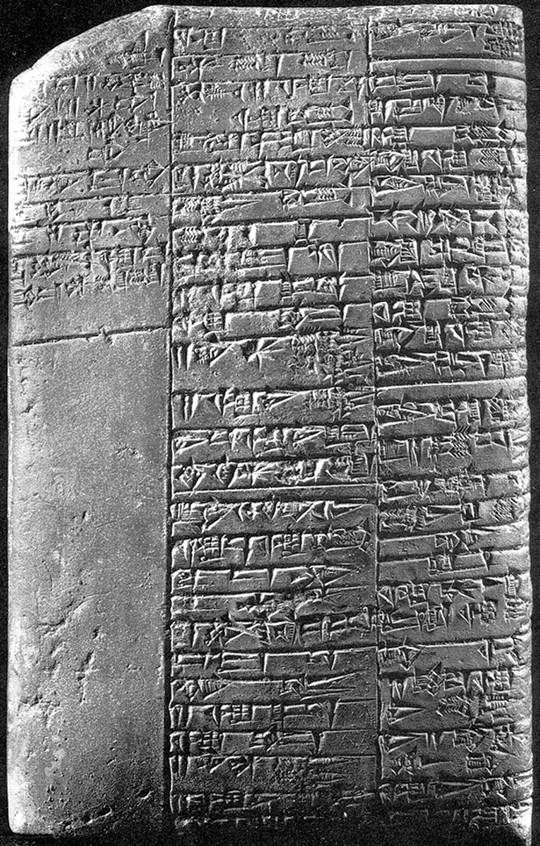

An example of these fees in three lines from the stele:

215: If a surgeon has made a deep incision in the body of a gentleman with a lancet of bronze and saves the man’s life or has opened a caruncle in the eye of a man with a lancet of bronze and saves the eye, he shall take ten shekels of silver.

216: If the patient is a freeman, he shall take 5 shekels of silver.

217: If the patient is a slave, the master of the slave shall give 2 shekels of silver to the surgeon.

Putting these fees into the context of the Babylonian economy, a decent middle-class dwelling could be had for 5 shekels a year, and a free craftsman might earn 10-14 shekels. Saving the life, or the sight of a gentleman was worth a year’s wages: saving a slave’s, just a couple of months.

But with high reward comes high risk. Performing an unsuccessful surgery, if the blame could not be passed onto the patient for offending the gods, ghosts, or demons, was subject to severe penalties. Unsurprisingly, but distastefully, the sliding scale applied here too, with the value of a human’s life depending on their social status. Negligently causing the death of a slave while trying to save them meant replacing them with one of equal value – an economic punishment. Doing the same to an aristocrat, however, risked losing a finger or even a hand – a corporal punishment. Beyond the corporal punishment aspect, unpleasant as that would have been, such a visible castigation was the equivalent of being struck off the medical register. The physician was stripped of the option to move to another city and start fresh by the mutilation that served as a very obvious advertisement of their medical malpractice.